EXPLORING THE “PAST OF THE FUTURE”

AT THE DISNEY HISTORY INSTITUTE

By Paul F. Anderson

|

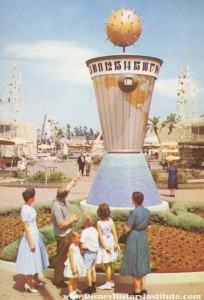

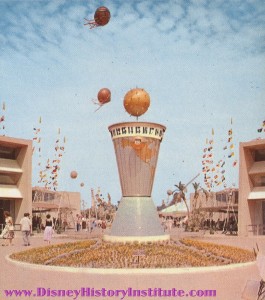

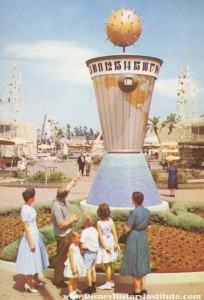

Tomorrowland Entrance Way, Fall 1955 (Slide). With a little bit of color provided by some well placed flowers by Bill Evans (and some super cool futuristic mid-century modern benches), the Clock of the World has a more regal feel to it than it did on Opening Day.

|

(Click on any picture for a high-resolution image)

Welcome, welcome foolish mortals (sorry, wrong land)! Welcome to the summer of Old Tomorrowland here at the Institute!

DHI readers are familiar with the oft told story of how Tomorrowland was the least developed land when Walt’s park opened in July of 1955, and how dissatisfied he was. Admiral Joe Fowler declared, “The Tomorrowland we opened with in 1955 was never a very happy situation for Walt.” There are numerous well-known stories about this situation, many of which have been repeated to no end, such as the humorous anecdote of Walt instructing his befuddled Imagineers to place Latin names on the weeds gracing the futuristic field of dirt held within Tomorrowland’s confines. Yes, on Opening Day Tomorrowland was a mess. We have heard the stories of how there just wasn’t enough time or money to finish all of Disneyland, so something had to be put on hold … and perhaps true to its namesake Tomorrowland was the realm that was put off until, well, tomorrow! But why!? Serious Disney Historians (Todd and I as well!) like to ask these difficult questions and then spend hours (or days) in search of an answer, and not just any answer (such as the approved narrative), but one that is supported by reasonable thought and the historical record (and frankly, one that has not been explored anywhere else).

I’ve often hypothesized that Tomorrowland’s virtual absence on July 17th was partly due to it being held hostage to Walt’s incredibly high standards…standards and ideals that resulted in an insane and wondrous attention to detail in every aspect of Disneyland. John Hench wrote “Walt knew that if details are missing or incorrect, guests won’t believe in the story, and that if one detail contradicts another, guests will feel let down or even deceived. This is why he insisted that even details that some designers thought no guest would notice … were important.”

|

|

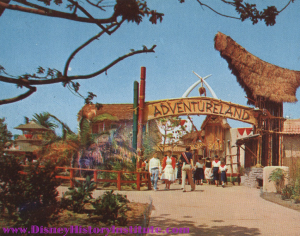

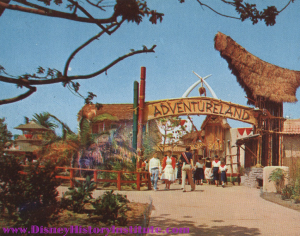

Adventureland Entrance Sign, Spring 1957 (Slide)

|

Think about this for a moment, and place yourself back in the fifties as an Imagineer (my ideal job, even better than being a Disney historian!!). You are tasked with creating a futuristic land of tomorrow, but it must be done with respect to Walt’s aforementioned sentiments about details. Where to start? Where is your basis for this world? What might you miss, such that Walt and the guests “won’t believe in the story”? What might guests “contradict” and as a result feel “let down or … deceived”? It quickly becomes apparent about the many pitfalls and problems that are bound to arise with your attempt to create this Land of Tomorrow … after all, those guys over on Adventureland and Frontierland have loads of details and established archetypes to choose from. “They got it easy!”

|

|

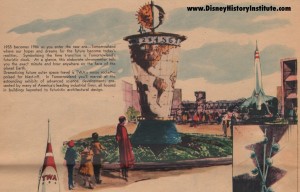

Tomorrowland Entrance Way, 1956

(Disneyland Guidebook 1956). The Clock

of the World with its futuristic satellite (sun)

for a crown that prophetically resembles the

Soviet Union’s Sputnik which was still a

year away from its October 1957 launch.

|

Even super Imagineer and Walt Disney favorite, Herb Ryman, recognized this struggle, and the difficulty it created even for him, when he lamented “I didn’t truly enjoy trying to delineate something for this Land of the Future.” Yet, this “Land of the Future” was an integral part of Walt’s magic kingdom, and it had to be done … somehow! According to Ryman, “If you show the past and Frontierland and Adventureland and Fantasyland, you’ve got to show the future.”

Back to your new career as a fifties-era Imagineer … coming up with a plausible story for this land is only the beginning, for once you have blue skied the future … you have to build it; and not just any old assembly job, mind you, the construction and fabrication must meet Walt’s rigid standards of attention to detail. Once again, it is easy to look over at our pals working on Frontierland and Adventureland, and how seemingly easy they have it. After all, it is considerably easier to build a frontier fort, right? You just buy a bunch of logs, dig holes, fill the holes with the logs, rope them up, and cut out a few windows and doors … Wallah! a fort (a bit simplistic, but you get the idea). Compare that to the erection and fabrication of space ships, planets, stars, flying saucers, time machines, a martian landscape, scenes from outer space, and so forth. It all sounds quite intriguing, doesn’t it? And it is … it is a wondrous story that has at its very core a man named Walt Disney; and I am sure DHI readers will look forward to each and every installment.

So sit back in your gravity-breaching rocket seat, strap yourself in for blast off, and get ready for a summer full of fantastic, fabulous, and futuristic fun! Because, fortunately we here at the Institute are historians and not Imagineers (well, bad example, Todd and I would love to be Imagineers working for Walt) and we are ready to tell the tale of Disney’s Land of the Future, and in doing so hopefully we will live up to Walt’s example of attention to detail. So enjoy the summer here at the Disney History Institute, while we chronicle for you the past of the future (got it?); an in depth look at the design, creation, and history of “Old” Tomorrowland. Let the exploration begin!

|

|

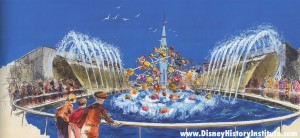

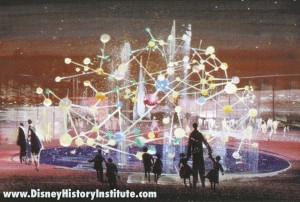

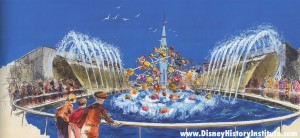

Tomorrowland Entrance Way by Herb Ryman, 1954. Absolutely fabulous WED concept for Walt’s favored idea of a Molecular Structure featuring fountains and tubes to go under the water in order to get to Tomorrowland. Simply Fabulous!

|

The Tomorrowland Entrance Way

Where does one begin an exploration of the “past of the future”? At the beginning, of course … and the beginning of Tomorrowland when we first gaze upon the land from the hub is the entrance way! Once again, DHI readers are (or should be) familiar with Walt’s wienie concept for Disneyland (also referred to as the “Hub principle”). At every vista within the happiest place on earth, Walt wanted a striking visual icon to pique our interest and draw us into that area or land (the wienie metaphor relates to a hot dog at the end of a stick and the mere site of this frankfurter creates a desire for it … especially if you are a rabidly hungry dog).

|

|

Adventureland Entrance Way, Summer 1955

(Disneyland in Natural Color, 1955) The

entrance concept at work, setting the story with

relative ease … and bamboo, thatched roofs, elephant

tusks, and by George, is that a shrunken head?

|

The first wienie to greet us at Disneyland is the Train Station high above a hill complete with the kinetic energy of old-fashioned steam engines arriving and departing non-stop. Stepping onto Main Street, we gaze upon another wienie, a fanciful Castle at the end of our vista beckoning us into this magical place. Finding ourselves at the Hub, there are four paths to the various realms of Disneyland, each with their own enticing wienie to draw us in, such as the Mark Twain Steamboat for Frontierland (Adventureland is up for debate!). For Tomorrowland the wienie is the strikingly futuristic TWA Rocket Ship to the Moon, easily the most stunning icon (save for perhaps the Castle) of any at Disneyland.

|

|

Frontierland Entrance Way, 1958 (Slide).

Again, the use of native materials that guests would

associate with Fronteirland, logs, lanterns, stockade, and

so forth, to set the scene. These same native materials

were not readily identifiable for Tomorrowland’s entrance

|

But before each land’s visual icon would pull us in, there is an entrance way. In some respects this entry portal is almost as important as the wienie. Walt wanted them to be designed in harmony with each land and while each was to be visually intriguing, it was to be scaled down from the wienie … it became the very first detail in each individual story. The entrance way was to deliver the opening act of just exactly what this land is all about, and beyond that, it should excite our senses of all the wonders that were to await us.

In the early creation and design process for the entrance ways, every land was sketched and created with relative ease … except for one. Yes, our old problem child Tomorrowland is back again, giving us Imagineers fits. After all, if the actual design of the land, and its contents, is experiencing a difficult creation process, it stands to reason that so should the entrance way. And just like Tomorrowland itself, the entrance way that made its debut on Opening Day did not live up to Walt’s standards or wishes.

|

|

Tomorrowland Entrance Way by Herb Ryman, 1954. A fabulous concept of the Molecular Structure and water fountains, only this time the tunnels under the water fall idea is absent due to budget constraints (not so fabulous!).

|

Walt had a very definite idea for the entrance way, as can be seen in one of the first major meetings devoted entirely to Tomorrowland, held on August 10, 1954. In attendance were Walt, Herb Ryman, Harper Goff, Bruce Bushman, and Richard Irvine (all Disney Legends save for Bushman). In this spirited “Land of Tomorrow” meeting Walt energetically outlined his plan to use the Hub principle, complete with the centerpiece of the hub to be a “Rocket Pylon with a revolving seat.” For the entrance way, Walt wanted a “Monorail Train.” Mind you, this is not the Monorail Train that would find its way to Disneyland in 1959, nor the fanciful one from the famed John Hench concept painting. There was no riding this Monorail, as it was, in fact, just set dressing for the entrance way; perhaps an artful allegory for the journey that awaited us inside the land. Established Disney history sort of suggests that the Monorail was part of early Disneyland thinking (but the technology simply did not exist), and therefore this concept of “Monorail as set dressing” seems a bit implausible; but by August of 1954 that is what it had become. As further proof, this notion is validated later in the meeting, where the attractions for Tomorrowland are discussed, outlined, and listed … and the Monorail is not being considered as an attraction or even listed as one; Walt’s futuristic transportation system was gone and would have to wait another five years. (For reference, this concept is identical to the Frontierland fort entrance way, where it was not an attraction but simply a set dressing, albeit one that people could enter and fire their Crockett muskets at imagined marauding indians.)

Within a month of this meeting, September 1955, Disneyland is seriously behind schedule, and the troubles for Tomorrowland are apparent. C.V. Wood, the first general manager of Disneyland, puts Tomorrowland on the back burner due to “practical concerns.” Beyond that, Roy’s financial people are reporting to Walt that they don’t believe the funds to finish the futuristic land will be available. The opening date for Disneyland has been frozen by the ABC network debut, and so to try and push back the opening date would be financial suicide–Disneyland, Inc. was seriously in need of that summer revenue. The result is that a decision is made to stop work on Tomorrowland and reschedule it as part of the 1956 expansion. We as Imagineers are assigned to other lands and attractions.

|

|

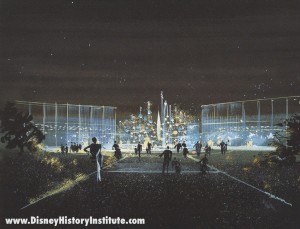

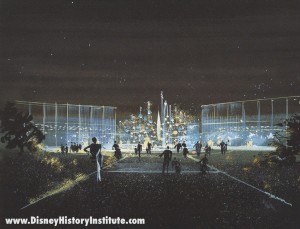

Tomorrowland Entrance Way by Herb Ryman, 1954. Sorry, we here at the Institute simply can not get enough of Herbert Dickens Ryman! Fantastic painting of Walt’s Molecule and Water (Scotch and Water?) entrance at night! Fabulous!

|

It doesn’t take Walt long to reverse this decision, believing that to open his Park only partially finished, would be an embarrassment. Against the advice of his financial people he instructs everybody to make Tomorrowland as attractive as possible and they would fix it later as the time became available. Tomorrow Land meetings with Walt begin again. To do this, which is in direct contradiction to the previous observation by John Hench about the attention to details, must have seriously rankled Walt’s soul; for our purposes it does illustrate the importance of Tomorrowland as an integral piece of Disneyland.

On December 14, 1954 a crucial meeting is held for the troubled realm. Starting almost from scratch on the entrance way Walt declares that he has decided “that we would explore the possibility of [a] molecular fountain for the entrance marquee of Tomorrow Land.” He reasons that it should be a protein molecular structure, because it “is symbolic of the staff of life for man.” In this meeting Walt appears rejuvenated in regards to Tomorrowland and he is fresh with new ideas, perhaps as a result of the work underway at the Studio on the Disneyland television episode “Man in Space.”

|

|

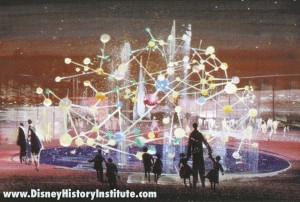

Tomorrowland Entrance Way, 1954. More impressionistic look at Walt’s idea for a Molecular Structure to grace the front of his World of Tomorrow, featuring wonderful use of color (Hench inspired, no doubt).

|

Walt suggests that the molecular structure for the entrance be made of different colored styrofoam balls (approximately 30 inches in diameter) and connected with plastic pipe. He continues that he would like to “electrify the structure so that it will have the appearance of traveling lights,” an idea which seems be an attempt to simulate the movement of electrons, protons, and neutrons.

It is brought up that Styrene is waterproof, and the meeting turns to creating a fanciful water fountain to go with the molecule. To protect “the customers from the water fountain, we plan to use a plastic covered walk through the fountain into the exhibit building.” This entrance way is quite exciting and very deserving of the future; it is a Walt idea that he would have loved to have accomplished, one that would aptly fit his dedication for the land of tomorrow as a “vista into a world of wondrous ideas, signifying man’s achievements…a step into the future, with predictions of constructive things to come.”

This covered walk through would allow guests to enter the world of tomorrow by passing through a molecule and water (sound familiar?). Walt loved this concept, so much so that he later revisited the idea for the Ford Pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. WED engineer Don Edgren explained: “Walt came up with this idea that he wanted to see a waterfall for the Ford Pavilion … our original design had this big waterfall cascading down and hitting the tunnels [where the cars would pass through]…it had good marquee and show value with all this water splashing around.”

|

|

Tomorrowland Entrance Way “Fountain of the 48 States” by Herb Ryman, 1954. Walt’s desire to use water is still represented, although the protein molecule has evaporated (along with much of Disneyland’s budget).

|

Within a short time the Imagineers began creating concept art for this awe-inspiring Walt idea to introduce guests to Tomorrowland, and quite a bit of this artwork survives today, even though the concept never made it from drawing board to reality. Sadly, even with all of these wonderful concepts by heavyweight Imagineers such as Ryman and Hench, the budget crunch was too severe. So once again, Tomorrowland was dumbed down as the search began for a cheaper entrance way.

|

|

Tomorrowland and Clock of the World, July 17, 1955 (Los Angeles newspaper insert). Fantastic publicity artwork, that is so representative of its era. The art was created for the opening of Disneyland.

|

An idea surfaced that incorporated the 48 states of the USA into the entrance way (seeing as how it was the world of tomorrow–1986 to be exact–one wonders why it was not the 50 states of the nation?) while still trying to embrace the use of water. Herb Ryman created an idea called “The Fountain of the 48 States” that kept the water works but whittled it all down into something less grandiose, two standard statuary fountains set off to each side of the entrance path (so rather than walking under a waterfall to the world of tomorrow, you would walk “next” to a waterfall … an idea that was used for the Magic Kingdom’s Tomorrowland, but it was discontinued because the wind created sideways waterfalls and drenched the guests).

|

Tomorrowland Entrance Clock of the World WED art.

Collection of Stan Jolley, who Todd and I interviewed &

almost cost us our lives. That story is here. Image from a

wonderful site, Scott Wolf’s Mouse Club House here. |

It soon became apparent to all that there was just no way to pay the water bill, and the fountains were dropped altogether. The 48 states idea was reused to fill space and put back by Richfield’s Autopia and the Space Bar (and quite a ways away from the entrance way). Each state in the union was represented by their flag that waved proudly atop a flag pole standing in an eight-pointed star planter and majestically named the “Court of Honor” (an E Ticket attraction no doubt, had the ticket book actually been around at the time!). This representation of individual states in our Union did ultimately find its way back to the entrance way, when in 1956 the Astro Jets attraction was placed square on top of the Court of Honor. The 48 flags were moved up to line a promenade that lead to the Tomorrowland entrance, where the odd-numbered states were lined up on the right side of the walkway and the even-numbered states on the left side of the walkway.

|

|

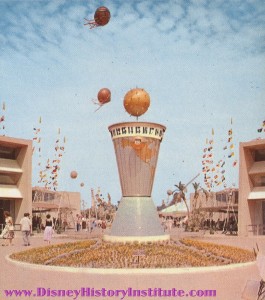

Tomorrowland Entrance Way, 1965 (Slide). Here featuring the state flags in the Court of Honor, the Clock of the World has served proudly for a decade while almost all of Tomorrowland around it has changed.

|

|

|

Tomorrowland Entrance Way Clock of the

World Summer 1955 (Disneyland in

Natural Color guidebook, 1955). After a year of

Imagineering the idea, this was the result, a

product of tight budgets and no time

|

Ideas for the entrance way still floated around through early 1955, but with time and money being in short supply the future had to wait, and wait it did, well into late spring of 1955. By this time Tomorrowland (besides perhaps the Richfield Autopia and TWA’s Rocket to the Moon) was being essentially slapped together at the last minute (which is a DHI story for, well, the future). The eventual entrance way became the seemingly uninspired Clock of the World, which although there is no evidence to support this, the Disney History Institute Editorial Board feels that it was either a)Intended as a set piece for another attraction, show, or building, or b)A last minute decision that was fabricated on the fly out of available materials (an extra large Dixie cup placed on top of an extra large pudding cup). Either way, with the slapdash assemblage of Tomorrowland in May, June, and July, the Clock was recruited to perform entrance way duties. (It should be noted that WED concept art exists showing the Clock of the World at the entrance to Tomorrowland–see above–so our DHI editorial board may be way off on this. Yet, even with the last-minute fill in theory, Walt still would have requested concept art to get a feel for how it might look and feel.)

|

|

Clock of the World’s Final Fanfare, September 1966.

After serving proudly the grand Clock that had stood

entrance at Walt’s Tomorrowland is mothballed,

never to be seen again (not even on eBay).

|

For something that may have been an afterthought (or at the very least a fourth or fifth choice) the Clock of the World stood proudly at the entrance of Tomorrowland for over a decade, finally being mothballed in September of 1966 in preparation for the arrival of New Tomorrowland in 1967.

In the end, it would seem that Walt thought that the Clock served its purpose, as he certainly had a plethora of opportunities to remove it and replace it with something more to his liking, including during the massive 1959 expansion, almost all of which centered in Tomorrowland. Interestingly, guests as well seemed to enjoy the iconic structure, as within the hallowed halls of the Disney History Institute there are literally hundreds of vacation slides and photos featuring happy visitors posing with the Clock. Maybe Walt knew something that we didn’t … something that the sheer abundance of these photos seem to suggest…that people liked the Clock of the World. And in the long run if the guests were happy, Walt was happy.

|

|

1958 Brussels World’s Fair Atomium, (WED Documentation Photo 1958). This centerpiece monument for the Brussels World’s Fair is very close in design to Walt’s original Molecular entrance way idea for Tomorrowland (no word on whether Atomium designer Andre Waterkeyn engaged in a bit of industrial espionage at WED). Of note, this photograph was taken by a team of WED designers that visited the Brussels World’s Fair for research purposes. They took hundreds of photographs for Walt (who later attended the Fair). Of significant interest to Walt and WED was the “Mouse” ride, which would later result in … well, we leave that for an upcoming “Old Tomorrowland Month” essay.

|

Enjoy! If you have thoughts, ideas, or questions post them up below. And for an ongoing historical discussion of Walt Disney and his creative legacy, head over to the DHI Facebook group. And make sure to check back for more essays and rare images on Old Tomorrowland. Thanks, Paul

A WHO’S WHO IN THIS STORY

This essay is filled with a virtual who’s who of important individuals in the history of early Disneyland. Rather than muddy up the essay with lots of explanations on who each person is (and many DHI readers are already aware of who they are), I decided to list the various people that are mentioned in the essay, along with a brief description of their purpose in working on Disneyland for Walt. Moreover, many on this list became friends to Todd and I, as have interviewed most everybody on the list (save for Woody, Irvine, and Bushman … and unfortunately Walt).

BILL EVANS – Original landscape architect for Disneyland.

DON EDGREN – Structural engineer, worked as an outside consultant for the creation and four years later was hired by WED.

C.V. “WOODY” WOOD – Disneyland’s first general manager, later sued by Walt Disney and Disneyland Inc for using proprietary information to create imitation Disney parks.

HERB RYMAN – Worked on Disney animated films in the 1930s and 1940s, later re-hired by Disney as an art director for the creation of Disneyland.

JOHN HENCH – Worked as on animated films (in background, layout, and effects) before transferring into WED where he worked as an art director.

BRUCE BUSHMAN – Worked on Disney animated films in the Layout department in the 1930s and 1940s before being transferred as the first permanent Disney artist onto the WED team in 1953.

WALT DISNEY – Roy Disney’s shorter and younger brother, was able to find effective employment outside of Roy’s financial and management circles at the Disney Studio.

HARPER GOFF – Art director, perhaps best known for his design of the Nautilus in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, and for his work on the Jungle Cruise.

RICHARD IRVINE – Art Director, originally from 20th Century Fox, who oversaw most activities at WED.

JOE FOWLER – retired Rear Admiral, with experience in ship and home contraction, originally hired as a consultant to build the Mark Twain Steamship in 1954, later oversaw most construction projects at Disneyland.

Great post!

Did they really mothball the clock of the world? I’ve never seen that photo before, I just assumed they destroyed it (well, they did trash the base). What do you suppose ultimately happened to it?

Thanks!