Pinocchio premiered on February 7, 1940 at the Center Theater in New York City, and in this essay I have pulled several artifacts from the DHI Archives that showcase additional exploitation done for the film. Moreover, to illustrate the importance of the promotion of the film–not only to the public, but sometimes, and more importantly, to the exhibitors–I have found some of Walt’s thoughts in regards to this.

|

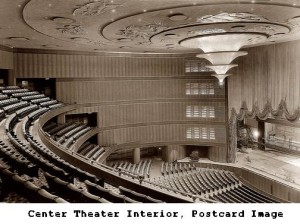

| 1940s Postcard, The Center Theater |

The Center Theater was owned by the Rockefellers and was on the South Block of the Rockefeller Center complex at 6th Avenue and 49th Street. It opened as the RKO Roxy Theatre in 1932, changed to the RKO Center Theater in 1933, and by 1934 was simply the Center Theater. The Art Deco movie palace was sort of the poor stepchild to the much larger and more lavish Radio City Music Hall–also part of the Rockefeller Center. Both theaters shared 1932 as their birth year and in 1933 both premiered King Kong, but other than this one shining moment, the Center could hardly compete with her big sister. The Music Hall had 2500 more seats more than the Center, a more elaborate interior, better location, and almost instant prestige within New York City social circles.

By 1934 the Center Theater was featuring second-run and double film programs, with only limited success. It was once said of the Center that no film really had a chance to succeed there , and RKO was certainly aware of this fact. The theater tried live theatrical shows, but the play did no better than the film, so RKO returned her to duty in the world of cinema. Pinocchio was the most notable film to play the Center after her return to the silver screen, and the little wooden boy became her best bet at a flashy premiere and return to any type of film glory (naked midgets aside). The Disney brothers would have much preferred the Radio City Music Hall, but RKO, noted at this time for its mismanagement, was not cooperative. By comparison, the film RKO chose to run at Radio City instead of Pinocchio was one of its own, the little-remembered Swiss Family Robinson (1942), starring Thomas Mitchell, Edna Best, Freddie Bartholomew, and Tim Holt. Th e film received mostly negative reviews, and within a few weeks was replaced by RKO’s Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1942), starring Raymond Massey and Gene Lockhart, and based on the Pulitzer Prize winning play. At the time, RKO and Disney were at odds and Roy and Walt did not feel that RKO was putting forth a fair effort towards promoting the Disney films, which was true. The correspondence between Walt and Roy from 1940 routinely deals with RKO problems and various ideas to get them to do their work. Of course, at the time RKO was having serious financial problems as well, as the entire film industry was reeling under the loss of the European market due to WWII.

e film received mostly negative reviews, and within a few weeks was replaced by RKO’s Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1942), starring Raymond Massey and Gene Lockhart, and based on the Pulitzer Prize winning play. At the time, RKO and Disney were at odds and Roy and Walt did not feel that RKO was putting forth a fair effort towards promoting the Disney films, which was true. The correspondence between Walt and Roy from 1940 routinely deals with RKO problems and various ideas to get them to do their work. Of course, at the time RKO was having serious financial problems as well, as the entire film industry was reeling under the loss of the European market due to WWII.

When Pinocchio was first in production in 1938, the money was rolling into the Studio because of receipts from the fairest of them all. But even with the new found wealth, exploitation was still a concern, as illustrated by the following story conference transcript. In this, Walt talks about the importance of the release of the film and the potential “trouble” of how exhibitor’s might view the film based on a proposed scene; and it is due to possible issues with how the film might be perceived, that the idea for the scene is dropped.

I find that Walt’s words give us one of the best ways to get to “know him.” When reading story conferences, one gets the picture of how involved Walt was and how almost everything at that Studio went through him–providing it was something he had decided to involve himself with. Because of this, I plan on posting from time to time excerpts from various story conference transcripts. (I have an almost complete run from the 1930s and 1940s, so if you have any requests, please email me.)

Meeting Held: 9:00 to 12:00 A.M. Thursday, January 6, 1938, in Projection Room #4.

Those Present: Walt, Ben Sharpsteen, Otto Englander, Bill Cottrell, Chas. Philippi, Dick Huemer, Joe Grant, Ted Sears, Homer Brightman, Walt Pfeiffer, Leo Ellis, Earl Hurd, Webb Smith, Herb Lamb, Ham Luske, Bianca, Leo Thiele, Cy Young, T. Hee, Mac Stewart, Frank Thomas, Fred Moore.

From Page 6 and 7:

Walt: We don’t have a winter sequence in it now, do we? I was wondering if we’d want to open on a winter sequence, the kids out on their sleds in the snow–and the next day, when he starts to school, it could be snowing. You have to look for things in there to give it production value. Would it interfere with the following stuff?

Cottrell: It might be winter at the end of the picture.

Walt: I thought if we opened with winter it would be winter at the end too.

Otto: It wouldn’t matter about Boobyland, because that’s a fairy tale country. It can be anything there.

Ham: It could be Christmas if you wanted it, at the start and finish.

Ted: If it were winter you could get a nice scene with the old man looking for him in the snow.

Homer: The kids could roll him up in a big snowball.

Dick: Why couldn’t it be Christmas?

Ham: They wouldn’t be going to school.

Ben: It could be just before Christmas and he’s making toys for the Christmas trade.

Walt: If it were Christmas it would accent the old man’s loneliness…You couldn’t show it in Russia though.

Tee: Wouldn’t you think that if it’s the holiday season, he wouldn’t sent Pinocchio to school the next day?

Walt: It wouldn’t necessarily be the next day. You could dissolve, and Geppetto’s sending him off to school.

Otto: Somebody said it shouldn’t be typed as a season picture, so that it can run all year.

Walt: That’s the trouble–the exhibitors will class it as a Christmas picture and only run it at Christmas time. Well, Heidi had Christmas in it–they had quite a sequence there of Christmas…It doesn’t matter, we were just trying to get something pictorial in here.

Ben: You could bring winter into Boobyland–they have ice cream.

Ted: If you want to use winter in part of it, when he comes home dejected, and goes to the shop and the shop is closed, would be a good time to do it.

Mac: You could handle it almost anyway–Boobyland won’t have to tie in with any other season–it’s pure fantasy–it could be anything.

Walt: One thing about having it Christmas here, it would bring out the old man’s loneliness.

Webb: It could be winter where he comes to the Fairy’s grave; it would look more desolate.

Walt: That’s really the best place, I believe, from a pictorial angle.

Cottrell: If you wanted to make this winter you could have it rainy there, drizzly rain–it would give a swell effect.

Webb: That storm on the ocean–if that was winter, you could get a lot of swell stuff on it.

Walt: Well, regardless of Christmas, what I think you ought to do with this is build some of these sequences a little stronger.

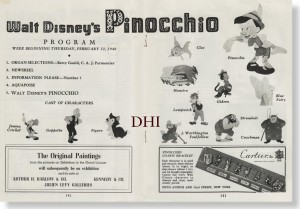

Tie-In Exploitation: “Original Paintings” On Exhibition The Grand Lounge And

Tie-In Exploitation: “Original Paintings” On Exhibition The Grand Lounge AndFor Sale!! Also Cartier On Fifth Avenue Offers A Charm Bracelet

Exploitation Knows No Bounds: Pinocchio Uses The Rockefeller Center Garage!

Exploitation Knows No Bounds: Pinocchio Uses The Rockefeller Center Garage!(I Do Not Recall Any Automobiles In Geppetto’s Peaceful Village? I

Guess We Should Be Thankful That Pinocchio Does Not Use Calvert Whiskey!)

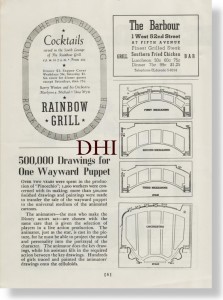

On the inside page of the program is an advertisement for Radio City Music Hall at Rockefeller Center and Robert E. Sherwood’s Abe Lincoln In Illinois. Since both movie houses were RKO theaters, the distributor also would exploit the concept of cross promotion. And the idea that there is no bad publicity, actually is very appropriate to the Golden Age of Hollywood. As such, any type of promotion that would get the word out, was welcome. The next DHI artifact is an example of this type of promotion, which today might be called “buzz.” It was produced as a “service from Public Relations Department, Fox West Coast Theatres” for Photoplay Appreciation Study Material. It was written by Mr. Vernon Steele, a well-known composer and conductor at the time, and an eminent music critic and acknowledged authority. In this “tract” Steele discusses the musical score to the two dueling films at the Rockefeller Center RKO theaters. Welcome publicity, as music was often a key to getting people to buy tickets to your film. The advertisement at the top of this essay is from Cue Magazine Manhattan Edition: The Weekly Magazine of New York Life, from February 10, 1940. It is from the last artifact from the Institute’s Archives for this essay. The periodical was intended to keep those living in Manhattan informed on entertainment: dining, dancing, concerts, plays, music, films, radio, and so forth. For the February 10th edition, the Disney publicity department managed to get the cover (an important promotional spot for a film–for more information on Disney’s use of the magazine, see DHI essays: Disney and the Magazine). The publication includes a positive review on Pinocchio (and a very negative review on Swiss Family Robinson), and a note on the cover: “Starring in ‘Pinocchio’, Walt Disney’s color-fantasy at the Center Theatre, are (left ro right) Jiminy Cricket, and, of course, Pinocchio himself. The reproduction is from a drawing made especially for CUE by the Disney studios.”

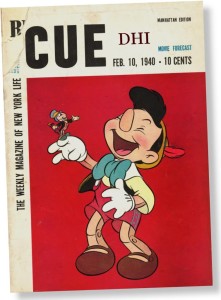

The advertisement at the top of this essay is from Cue Magazine Manhattan Edition: The Weekly Magazine of New York Life, from February 10, 1940. It is from the last artifact from the Institute’s Archives for this essay. The periodical was intended to keep those living in Manhattan informed on entertainment: dining, dancing, concerts, plays, music, films, radio, and so forth. For the February 10th edition, the Disney publicity department managed to get the cover (an important promotional spot for a film–for more information on Disney’s use of the magazine, see DHI essays: Disney and the Magazine). The publication includes a positive review on Pinocchio (and a very negative review on Swiss Family Robinson), and a note on the cover: “Starring in ‘Pinocchio’, Walt Disney’s color-fantasy at the Center Theatre, are (left ro right) Jiminy Cricket, and, of course, Pinocchio himself. The reproduction is from a drawing made especially for CUE by the Disney studios.”

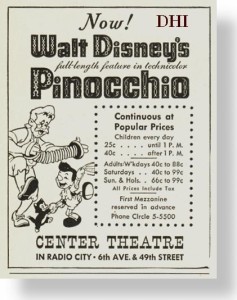

All of the exploitation work (and this essay only looks at the proverbial “tip of the iceberg”) was all for not. The war had consumed the European market, and Pinocchio did not strike the fancy of an American public that was worried with the world situation. The Studio continued to work ardently at promoting Pinocchio, but found little to no help from RKO. Roy and Walt at one point became personally involved with decision making on a scale that normally they would not have even worried about. Before the opening, they were worried about finances, and the decision was made to raise the price of tickets at the two Hollywood Theaters Pinocchio opened at, the Hillstreet Theater and the Pantages. The brothers felt that a premium ticket price would be paid by the public to see a Disney animated feature, so the cost of $1.10 was decided upon (compare this to the “Popular Prices” in the Center Theatre ad heading this essay). A February 14, 1940 memo to Walt, from George Morris (secretary/treasurer), suggested that the price was restrictive, and many patrons that were interviewed changed their minds after seeing the price and chose a cheaper film instead. The price was lowered; but in the end, it didn’t matter. The extraneous variables were too out of control, and the film lost a great deal of money–funds that the Studio did not have to lose. This loss, combined with other factors from 1940 and 1941, put the Disney brothers on the brink of bankruptcy. Perhaps, an essay for another day.

Is this the only story conference you have on Pinocchio?

Do you have a scan of the text of Vernon Steele discussion?