The Disney-MGM Studio Backlot in Burbank

Part Four: Then Come The Real Problems!

by Todd James Pierce

The real problems for Disney emerged in the final months of 1987.

Though the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot had originally been budgeted at $150 million to $300 million, in September Disney received new estimates from architecture, engineering, and construction firms that placed the price tag at $611 million. The price tag for some areas, such as the Hyperdrome, originally budgeted at $205 to $251 per square foot, had more than doubled. To add to the bad news, Disney’s original plan to lease out part of the Backlot to traditional retailers wasn’t working out so well, as many retailers were unwilling to invest in such an unusual new venture. Taken together, these two reports forced Disney to scale back its plans.

In October, executives at MGM added to Disney’s troubles by demanding that the MGM name be removed from the California park. MGM-UA Chairman Lee Rich claimed that the agreement to partner with Disney for a park in Florida did not give Disney the right to build a second MGM park in California. “We were very upset about it,” Rich told the press. “We’re going to do anything we can to get them not to use it.”

For Disney the only good news came from the courts. On Jan 20, 1988, a judge dismissed one of the MCA lawsuits. Because Disney was only developing preliminary plans, the judge concluded, no environmental impact report was yet required.

After the ruling, Burbank Mayor Michael Hastings said to a group of reporters: “We were challenged with a bogus lawsuit, but we won. I hope now we can bury the hatchet with MCA.”

But the remaining MCA lawsuit, the escalating construction costs, the disagreements with MGM-UA, and the lack of retail co-investment were causing Michael Eisner to have his own doubts about this new complex in Burbank. During January and February, Disney entered talks with international retailers—including London’s famous Harrods department store—about participating in the Burbank project, but these talks did not produce enough meaningful retail partnerships to support the site.

On Thursday, February 18, 1988, to an audience of shareholders, Michael Eisner explained that the Burbank center had temporarily taken a backseat to larger projects, such as the new Disney-MGM park in Florida and Euro-Disneyland. But he believed that the center would move forward. He even said that there was a “better than 50% probability that an urban entertainment center will get under way in Burbank this year.” He explained that the problem wasn’t one of corporate will, rather of limited talent. “I would say it’s some time off before we break ground, a couple of years maybe. We’re designing it all, but I would say that instead of having 40 people on it, we have five people on it.”

The very next day—just hours after Eisner mapped out a timeline to groundbreaking—Disney convened a meeting with its economic team to sort out the mess that the Studio Backlot project was becoming. Though the economic team believed that the retail, dining and club experience might prove economically feasible for a Burbank location, they had deep concerns over the teen-oriented Hyperdrome and the tourist-directed studio attractions. Even with the most generous cost estimations, they concluded that the Hyperdrome would have to be built for no more than $354 per square foot and Cinemagic for no more than $477 per square foot. It is now unclear if the economists were referring to the Cinefantasy or Magic of Disney sections—or if in a later version of the complex these two areas were combined into one movie-related gated area with a combined name. Regardless, both of these figures were far less than was needed to create substantial attraction areas. In short, the team advised that there would not be a sufficient audience base to make those two areas profitable in its current location.

Within days, rumors started that the Disney project in Burbank was in deep trouble. City Manager Bud Ovrom recalls: “I had an intuitive feeling that things were not going well. Whenever I went over to Disney to meet with Alan Epstein, there were no renderings of the project on the walls, no models on the tables.”

Mayor Hastings vividly remembers the day when Disney representatives came to City Hall with plans for a new corporate office building. When the mayor asked about progress on the Burbank Studio Backlot, a Disney manager responded, “I wish you wouldn’t ask me that question.”

After investing 22,000 man-hours in planning and $2.5m in market research and economic analyses, on Friday, April 8, Disney publicly announced what most everyone in Burbank already knew, that it was dropping plans to develop the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot.

The official reason was money. To complete the park as originally designed would cost over $600 million. To build a scaled-back version would reduce the total number of guests—and therefore lower the park’s earning potential. “When we started playing around with the concept,” Eisner explained, “and eliminating things like the Burbank Ocean, it started becoming a project that it would not take Disney to do. With Disney, we have to exceed our guests’ expectations, they expect a lot.”

But there were at least three other possible reasons: (1) At the start of 1988, Disney had purchased the Wrather Corporation holdings with an Australian investment firm for a 50-50 split. Analysts speculated that Disney’s prime and perhaps only interest was the Disneyland Hotel, with the Wrather oil, gas and Long Beach properties going to the Australian investment team. But by February, Disney owned the Wrather Corp holdings outright and was beginning to explore ways to develop the land in Long Beach into a new park–one that would include a retail shopping district similar to the one proposed in Burbank. (2) In recent months, Disney had entered into an agreement to build a European Disney park near Paris, which would drain money and creative resources from the company. Disney was also very quietly exploring how to add a “World’s Fair” style park to its resort in California, a project that would later hold the name WESTCOT. Simply to manage its talent, Disney may have needed to prioritize its developments. And (3) it’s also possible the Disney execs finally came to their senses, realizing that a longstanding rivalry with MCA might have lured them into an extremely expensive park proposal for Burbank.

Hours after the Disney announcement, one Burbank Councilman bitterly quipped, “Let’s see if MCA will come running over now with their checkbook.”

In a news release, MCA claimed that they hadn’t yet come to a decision “regarding its future actions in Burbank,” nor had they decided on a date for “concluding its consideration of the [Burbank mall] site.” Needless to say, MCA never made an offer on the Burbank property. From their actions, it was clear that their only interest in the site was to prevent Disney from opening its own studio-based park near Universal Studios.

With the Disney deal dead, the City of Burbank solicited bids from developers for a retail entertainment complex. They received many. Most proposed traditional mall-type developments, though one did propose to build a marine park complete with a giant aquarium and a dolphin show. The city would eventually approve plans for a modern mall with national chain stores and a multi-screen theater complex. Years later, Mayor Hastings would express his disappointment over Disney’s decision to abandon the project. “They promised us the world and then they pulled the rug. It was a very cold shower for the community and the community government.”

In 1989, the Walt Disney Company opened the Disney-MGM Studios in Florida (now called Disney’s Hollywood Studios) to mostly tepid reviews. The park included many attractions also slated for the proposed Burbank park, including a working animation studio, The Great Movie Ride, and backlot dining and retail establishments. Many guests noted that the park seemed incomplete and did not yet offer enough for a full day’s entertainment.

In 1990, MCA opened Universal Studios Florida to mostly positive reviews. Also in 1990, MCA developed plans to create new free-standing rides for its park in California to better compete with Disneyland.

Nine years after the failure of the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot, Disney again set out to conquer regional retail space. This time they were armed with a new product called DisneyQuest—which was an indoor video theme park. Each DisneyQuest would feature cutting-edge games and interactive ride simulators. The first DisneyQuest opened in a five-story, windowless industrial building at Walt Disney World in 1998. A second opened in Chicago the following year. Disney broke ground for a Philadelphia location but abandoned the project before it was completed. Another was planned for the Disneyland Resort but never built. Beyond these, Disney sought out sites in large American cities—including sites in Times Square and Rockefeller Center—as the company believed these regional video parks would offer guests far from California and Florida a way to enjoy a Disney-themed experience without a lengthy vacation. But the DisneyQuest parks did not meet company profit expectations.

The final remnants of the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot can be found in Anaheim. When designing Disney’s California Adventure, Imagineers revisited the plans for the Burbank Backlot and absorbed the California Boardwalk and giant Ferris wheel concepts into the plans for the new Anaheim park. Toward the back of Disney’s California Adventure, in an area called Paradise Pier, guests can ride a giant Ferris wheel that dips down into a manmade lake—just like the one originally planned for the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot.

One year after Disney dropped plans to build the Backlot center in Burbank, Universal announced it would build a new studio park in either London or Paris, essentially following Disney into the European market. Frank Stanek, an executive vice president at MCA, claimed that their European “venture has nothing to do with Disney.” For its part, Tom Deegan at Disney attempted to downplay their rivalry, essentially dismissing MCA as an unworthy rival: “We don’t look on MCA as competition. We really don’t think it’s worth commenting on. They’ve been talking about doing things—Japan, Europe, Florida—for years. We don’t consider them serious competition.”

But hardly anyone in the industry believed it. In summing up the rivalry between Disney and MCA in 1989, Raymond Katz, a New York analyst, put it this way: “I think MCA would like to give Mickey Mouse a black eye…Disney is a fairly recognized brand name, and they [MCA] are taking it on head-to-head. They’re going wherever Disney goes.”

=== === === === ===

The Entire Disney-MGM Backlot Series Now Available On The DHI Podcast

=== === === === ===

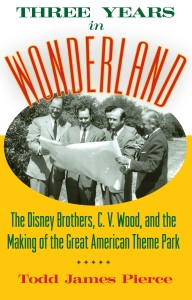

This article is part of the DHI reboot: From January through April, I’ll be posting up new articles and releasing new podcasts each week. I’m between projects, and with THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND coming out in March, I finally have more time to devote to the blog. Most regular visitors here already know that THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success.

This article is part of the DHI reboot: From January through April, I’ll be posting up new articles and releasing new podcasts each week. I’m between projects, and with THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND coming out in March, I finally have more time to devote to the blog. Most regular visitors here already know that THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success.

I should also point out that this DHI multi-part article is a substantial expansion to the original Disney/Universal article on the Studio Backlot that I wrote for Jim Hill Media in 2008. In the past eight years, I’ve discovered many more elements that contribute to this fascinating story. The original article, clocking in at twenty pages, is now over forty.

Lastly, even when things are slow on the blog, the DHI Facebook Group is always jumping. –TJP

Saddled with a few hours of daily commute time to fill, I consume many podcasts. As a Disneyphile (word confirmation?) I have worked my way through both the good and giggly podcasts of Disney fandom. Well, some of the giggle ones, anyway.

I somehow just discovered the DHI podcast, and am working my way through time to the present – have to say that I am loving it!

Wonderful reading and writing style, detail and topics. So, Thank You!

Amazing article!