The Disney-MGM Studio Backlot in Burbank

Part Three: Behold, The Studio Backlot!

by Todd James Pierce

Despite the two MCA lawsuits, Disney continued to develop plans for the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot in Burbank. For the Texposition mall in Dallas, Disney had used the term “festival marketplace” to categorize the project. But as the Burbank project grew, they understood that the term “marketplace” no longer described their plans. It was far more of an amusement park than a mall, though the Rouse team was still charged with bringing in high quality retail shops and restaurants, most of which would be arranged in an upscale mall quadrant now called Provedencia. Disney didn’t want to use the terms “park” or “theme park” to describe the project, in part because the project was largely indoors and in part so families wouldn’t consider this an alternative to a full Disneyland vacation. Instead they decided on the term “Entertainment Center,” though to the casual observer the project looked largely like a small theme park.

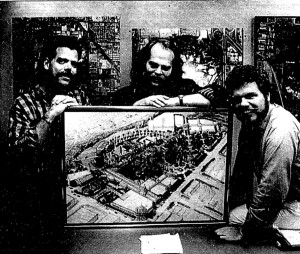

At the creative helm were two relatively-young Imagineers: Joe Rohde and Rick Rothschild. Their mission was to seamlessly integrate Disney-style entertainment into a downtown urban environment. To accomplish this, Rohde and Rothschild spent hours on the top floors of nearby buildings to get a birds eye view of the proposed Disney parcel. At that time, much of the land was little more than a weedy lot, bordered by the Golden State Freeway and the Burbank Civic Center. Specifically the two Imagineers wanted to observe how traffic and pedestrians moved around the 40-acre parcel. The proposed center would station most of the retail stores along the outside border of the property to better accommodate local shoppers. “All the crazy stuff will be in the middle,” Rohde explained.

The proposed center, growing in complexity, was now massive, with multiple themed areas both inside and outdoors. Plans for the project were fluid, conceptual, quickly changing. By fall, the center was slated to include 172,000 square feet of themed retail space, 145,000 square feet of restaurants and bars, 94,000 square feet of nightclubs, plus a yet undetermined number of square feet devoted to attractions, multiplex screens, and other entertainments. The attractions areas would be both in- and outdoors, but designers now sought to group some of the indoor attractions into four areas, even if those four areas would each have multiple visual themes.

One large area, now tentatively called the Hyperdrome, would be a gated teen club. Though originally pitched as an underage dance facility—similar to Videopolis at Disneyland—it grew to include thrill rides and technology-based experiences for young adults. Disney estimated that the market breakdown would include an audience of 85% local residents and 15% tourists, a young demographic that might otherwise find entertainment at a nearby Six Flags park. Early plans placed the Hyperdrome at 110,000 square feet, though planners understood that this area was likely too small to meet its attendance goal of 1.5 million guests per year.

The second area, The World of Disney, another gated section, would collect up the studio-based entertainment. There would be at least three attractions: The Disney Story, The Magic of Moviemaking, and the Disney Center Tour, which would likely include a tour of the Disney Channel TV facilities. Unlike the retail and dining sections, this area would be largely designed for tourists.

The third gated area, added to the plans after the presentation to the Burbank Redevelopment Agency, was tentatively titled Cinefantasy, with attractions themed to Science Fiction. In Fall 1987, it was the least developed attractions area of the complex, but notes suggest that it would include a special format theater, a museum of science fiction movie props and costumes, and other offerings. This, too, would be designed for tourists.

Lastly, the complex would collect various rides into its outdoor Burbank Ocean area, a section that resembled a seaside amusement park. Though the “Ocean” was only 18-inches deep guests would be able to take motorized rowboats from the boardwalk out to the restaurant at the edge of the falls. On the boardwalk, guests would find a funhouse with high-tech illusions. Along the perimeter would be a bumper car highway, where guests could crash cars together on an open road. At the edge of the Ocean, atop the six story structure, would sit an enormous Ferris wheel that would dip down into the manmade lake, before rising a hundred-feet above ground.

Taking a cue from the new Pleasure Island development at Walt Disney World, Imagineers solidified the backstory and overall theme for the Burbank property in such a way as to give the park its own mythology and meaning.

Though early on Imagineers played with the idea that the complex might be presented as a fictitious studio founded by Walt Disney in the 1930s, that idea was dropped—probably so as not to cause confusion with the historic figure of Walt Disney. Eventually the backstory for the Burbank Backlot, as presented to the press, went like this:

In the late 1890s, a few residents of Burbank—or whatever Burbank was called in the 1890s—discovered gold. Shortly after their discovery, people flocked to the area. A western town developed. And some twenty or thirty years later, long after all of the gold was mined, the locals considered the best way to invest their grand fortune. Their answer: to make movies. And to make these movies, they created a backlot complete with a Parisian lane, a Spanish street, and a California boardwalk. Somewhat later they also built an early TV and radio studio. But then, during hard times, the studio went out of business—only to be rediscovered by Disney, who transformed it into an entertainment complex.

For guests, the backstory would explain the collage of architectural styles and the unusual use of many buildings: an American-style restaurant housed in a Parisian apartment building, a souvenir shop shoehorned into a Spanish hut, and the California boardwalk arranged atop a six story building. Even the mock “Ocean” had a story: it was once a special effects tank owned by the old studio.

For the press, Rick Rothschild spelled it out simply: the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot would be a mythical place, “where great movies of the past were filmed.” The shops, restaurants, nightclubs, and show buildings would be tucked into old backlot facades. “That way,” he continued, “we could incorporate the variety of themes, make streets interchangeable.”

As the Disney-Rouse plans came together—and as Micahael Eisner saw potential profit in more urban parks—Disney announced that they were looking to further franchise this concept, though of course, future urban centers would not include the TV studio and animation complex. Specifically, Disney announced that it was now pursuing developments in Chicago, Philadelphia, and San Antonio. “We’ll be doing more of these,” Rothschild explained to a local reporter, “and we will fit them to the needs of the community.”

By this point, the ambitions of two giants in the same industry were poorly controlled. The damage from the Disney/MCA rivalry, both in terms of expense and public relations problems, was being absorbed on both sides. In July, 1987, Disneys CEO Michael Eisner and MCA President Sidney Sheinberg attended a two-hour breakfast meeting at the Registry Hotel, not far from MCA’s headquarters, to see if there might be a way to move forward with Universal and Disney working together on at least one project. As the meeting was held in public space, much of Hollywood was soon curious as to why these two bitter rivals were talking . Disney Vice President Erwin Okun confirmed to the press that the meeting had been called by Eisner “because he thought it would be constructive.” Sheinberg also admitted, “We did have meetings designed to see whether or not we couldn’t combine these attractions [in Florida] when it became patently clear what they [Disney] were going to do.” Though both men agreed never to discuss meeting details with the press, sources at MCA leaked that “Disney offered to give MCA a royalty but no active partnership in a combined tour” in Orlando.

With this, MCA had no choice but to turn down this paltry—and somewhat insulting—proposal. And as a result, Disney muscled ahead with its plans to develop studio parks in Florida and California.

The next development caught many individuals, especially those at Disney, by surprise. In October, Burbank citizens began to receive pamphlets that described the mess Disney’s Backlot would cause for local residents, urging them to oppose the Disney development as a type of grassroots political movement.

With glossy photos and color illustrations, the first pamphlet claimed that the Disney development “will turn virtually all of downtown Burbank into a massive tourist complex and require a tax subsidy of over one-hundred million dollars.” It also claimed that the secret deal was finalized “after less than 30 minutes of council discussion” with “no competitive bidding.”

The cover of the second pamphlet featured a photo of the Disneyland castle with the caption: “It’s a nice place to visit.” The interior, however, included images of dingy hotels, cheap liquor stores, and tacky tourist shops beside a single line of text: “But you wouldn’t want to live there.”

A third pamphlet emphasized the environmental damage the Backlot would cause to the region.

And fourth reiterated the major points made in the first three mailings.

The fliers were sent by a new political action group known as the “Friends of Burbank,” who listed as their only address a private mail drop. From the start Burbank officials felt they knew who was behind the attack: “Somebody, and I assume it’s MCA,” Councilwoman Mary Lou Howard said, “is spending a lot of money to get their point across.”

Two weeks after the first brochure was mailed, city officials were able to prove that, in fact, MCA was behind the “Friends of Burbank” campaign.

Shamed into admitting fault, MCA attorney Dan Shapiro begrudgingly offered a statement to the press: “Obviously, we would have preferred to have a full discussion of the issues, but since Burbank will not do it, we decided to get the word out any way we could. We knew there would be consequences, but we are prepared to accept them.”

Another time, feigning community good will, Shapiro explained that the reason MCA hid behind a fake business name for the mailings was because “we thought the issue would have become MCA vs. Disney, which we did not want. There are serious questions about whether the citizens should be subsidizing a Disney project.” He also claimed that MCA “always intended to disclose its role in the mailings after Tuesday’s council meeting.”

The mailings, it was revealed, cost MCA roughly $20,000 and went out to 43,000 Burbank residents. Ironically, some newspapers reporting on this revelation also pointed out that Universal was now in the early stages of planning its own outdoor “entertainment and retail complex,” smaller but similar to that proposed by Disney. Years later this project would be called the CityWalk, a movie-themed upscale mall filled with entertainment.

Clearly gloating, Michael Eisner issued a statement for Disney: “This activity is totally uncharacteristic of any major American corporation. Therefore, we’re at a loss for words.”

Though the City of Burbank had originally contacted Eisner with the hopes that Disney would somehow help save a local mall project, they now found themselves in the middle of a bitter battle between two corporate rivals. One city attorney, still not grasping the overall context, told the press that these ongoing lawsuits were an “obvious attempt by a multinational corporate conglomerate to dash the dreams of a city that wants a retail shopping center.”

=== === === === ===

In a few days: Chapter Four – Then Come The Real Problems!

Also Available On The DHI Podcast

=== === === === ===

This article is part of the DHI reboot: From January through April, I’ll be posting up new articles and releasing new podcasts each week. I’m between projects, and with THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND coming out in March, I finally have more time to devote to the blog. Most regular visitors here already know that THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success.

This article is part of the DHI reboot: From January through April, I’ll be posting up new articles and releasing new podcasts each week. I’m between projects, and with THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND coming out in March, I finally have more time to devote to the blog. Most regular visitors here already know that THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success.

I should also point out that this DHI multi-part article is a substantial expansion to the original Disney/Universal article on the Studio Backlot that I wrote for Jim Hill Media in 2008. In the past eight years, I’ve discovered many more elements that contribute to this fascinating story. The original article, clocking in at twenty pages, is now over forty.

Lastly, even when things are slow on the blog, the DHI Facebook Group is always jumping. –TJP

This is a terrific series! Looking forward to part 4.