The Disney-MGM Studio Backlot in Burbank

PART ONE

by Todd James Pierce

PROLOGUE

Years before Disneyland, Walt briefly explored the idea of using trains to offer guests a brief tour of his animation studio in Burbank.

Though the idea had likely been percolating for a while, the concept was brought into play in 1948. That spring he traveled up to see the privately-owned Wildcat Railroad in Los Gatos, California. The Wildcat was a one-third scale railroad run by Billy Jones, a northern Californian railroad man, who had set it up mainly for children. On select weekends, he operated the train free-of-charge, accepting only donations from families wishing to venture out on his ranch. Something in this set up intrigued Walt, a train with enough track to transform a simple ride into a small-scale scenic adventure.

Walt was interested enough to ask if Jones might help him acquire a steam engine and rolling stock of his own. “Personally,” Walt added in a letter, “I envy you for having the courage to do what you want.” At the time, Jones had either just bought—or was in the process of buying—multiple one-third scale engines and cars from the estate of an eccentric rail fan, Louis Mac Dermot who had once managed the scenic train operation at the 1915 Pan Pacific Exposition and subsequently at the Alameda County Zoo in Oakland. Jones promised to keep Walt in his thoughts.

A few weeks later Walt received a wire that Billy Jones knew where Walt could buy a one-third scale engine for $2,500. Like the one Jones operated, it was an amusement train, once operated at a local zoo, not a backyard model, and would require a sizeable piece of land, like the studio, to layout a track course. Walt considered the idea for a while, but ultimately decided to pass: he was busy with other things that year, most notably returning the studio to full feature-length animation with Cinderella.

In the years that followed, Walt would find ways to present the craft of animation to the public: a traveling museum exhibit, displays at Disneyland, and behind-the-scenes episodes on his weekly TV series. But he would never adapt the studio to received daily guests curious about animation. The idea, however, would stay with the studio, an idea that would return twenty years after Walt’s death, when a newly-minted CEO named Michael Eisner was trying to push the company in new directions.

Chapter One

So Begins The War

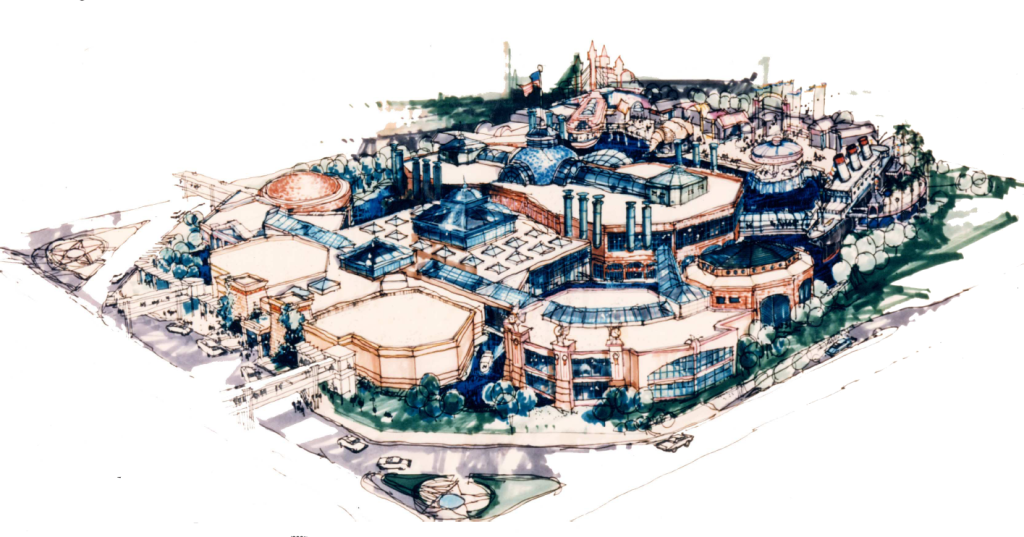

The Disney-MGM Studio Backlot in Burbank might be a mere footnote in the larger rivalry between Universal Studios and the Walt Disney Company, except that the Studio Backlot was a beautiful example of 1980’s excess and imagination, a sprawling work of cinematic fantasy pushed up against the I-5 Freeway. Like Westcot in Anaheim and Port Disney in Long Beach, the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot was a massive tourist complex that Disney designed but never built. At the heart of the story are two film companies, Disney and MCA, who had learned that tourist attractions could be a more reliable source of income than movies, particularly if those attractions were built in Southern California or Florida.

Rivalries between the two companies first sparked in the early 1980s, when MCA (parent company of Universal) developed plans to build “Universal City – Florida” in Orlando, a combination theme park and working studio that would compete head-to-head with Walt Disney World. MCA’s intentions were well known inside the outdoor amusement industry: to expand its theme park offerings for an east coast audience, just like Disney had during the previous decade. At the time, Universal Studios in Hollywood was the third most popular theme park in the country, trailing only Disneyland and the Magic Kingdom. Not only had MCA purchased four hundred acres in Orlando, they had begun hiring ride designers trained at Walt Disney Imagineering in the hopes of bringing a higher level of artistic and technical sophistication to their attractions.

The initial plans for the Universal Florida property were styled after the studio park they owned in California, complete with a backlot tram tour, a make-up show, a special effects demonstration, a stunt spectacular, and various walk-through exhibits. To grant the park credibility as a working film studio, the Florida property would also house sound stages for film and TV production. In other words, the MCA Recreation Group initially intended to build a larger version of the industrial tour it had developed in California, only more focused on tourism than on film production.

But these plans began to shift as MCA hired designers who had been trained by Walt Disney Imagineering, such as Peter Alexander and Gary Goddard. Under their guidance, MCA abandoned the plan to clone their California studio tour in Florida in favor of developing something that more closely resembled a Disney-style park. Instead of a tram tour, MCA would develop stand-alone rides. Instead of the studio-industrial environment, MCA would develop environmental theming. But once MCA execs warmed to these suggestions, they didn’t simply want Disney-styled designs; they wanted Disney-style technology as well.

To add technological sophistication to their attractions, MCA contracted with Sequoia Creative to build audio-animatronic figures, initially for its studio park in California. Sequoia was filled with talent that had been trained at Walt Disney Imagineering, including future Disney Legend Bob Gurr. This pattern of employing talent closely associated with Disney clearly telegraphed MCA’s ambitions: not only were they muscling in on the Mouse’s territory in Florida, they were exploring the Disney park model to re-envision their studio tour.

But before the MCA Recreation Group announced plans to build a movie-related theme park in Florida, Disney beat them to the punch. In 1985 Disney execs announced they would build their own Hollywood-inspired park in Florida, what was then called the Disney-MGM Studio Tour. To design this park, Disney borrowed heavily from industrial tour concepts that Universal had pioneered in California—including a backlot tram tour, various stunt and effect shows, and the opportunity for guests to see production crews work on actual film and TV shows. This new Disney-MGM park appeared modeled after the California version of the Universal park or perhaps even an early plan for their Florida park, one that Universal execs contended that Eisner, before moving to Disney, likely saw at a Universal meeting. “There was a horrible sense of personal and corporate betrayal,” MCA President Sidney Sheinberg would later say about the similarities between the proposed Disney park and the studio park designed by Universal.

For MCA the problems didn’t end there. To make the park more attractive to a wide range of guests, Disney had acquired rights to use film properties held by MGM, United Artists and Twentieth-Century Fox, including such titles as The Wizard of Oz, Alien, and James Bond. In essence, Disney signaled that they would make a theme park with properties owned by some of the most powerful studios in Hollywood, leaving Universal the difficult task of building a similar park twelve miles away relying primarily on properties it already owned.

Observers would note that he early announcement of the Disney park, four years before it opened, was intended to do one thing: discourage Universal from developing its own Florida park in Disney’s backyard. For a while this plan seemed to work. Seven months after the Disney announcement, a reporter for the Orlando Sentinel confirmed that “although MCA has not thrown in the towel officially, insiders are betting that the Disney attraction will negate the Universal City-Florida project—even though MCA has spent more than $40 million on [plans to develop] it.”

MCA executives, however, didn’t back down. To capitalize and expand the project, they quietly talked with Florida Governor Bob Graham about state investment in the Universal park, hoping that the Governor would believe that the state of Florida would benefit from making Orlando an even larger tourist destination. The Governor agreed. Under his leadership, government officials made tentative arrangements to loan MCA $150 million from the state pension fund to develop its park in Orlando. The loan would be secured by a first mortgage on the 423-acres that MCA owned in the state. In essence, Florida was offering MCA an enormous low-interest loan to not only keep the Universal City project alive but to allow MCA to build an even larger park than originally planned. Only once these plans were made public, Disney used its political muscle to scuttle the deal.

This tactic infuriated MCA President, Sidney Sheinberg. At a press conference, he lambasted Florida officials: “Disney’s ability to decimate you by acting in a predatory way is chilling,” he snipped. “Do you really want a little mouse to become one large, ravenous rat?” He concluded his rant by threatening to abandon the Universal project for good if the board that governs the state pension fund decided to rescind its investment offer for Universal City – Florida. He suggested that he might sue Disney for copyright infringement, claiming that the proposed Disney studio tour relied on a park model over which MCA held propriety ownership. When a reporter asked, perhaps jokingly, if entertainment companies ever filed antitrust suits against each other, Sheinberg remarked: “We could be the first.”

Over the following year, MCA repeatedly tweaked Disney about the possibility of a Universal park moving into Orlando. In March, 1986, MCA went so far as to place a full-page color ad in the Orlando Sentinel for the grand opening of its King Kong attraction…an attraction that was opening 3,000 miles away, at its park in California. The ad could only serve one purpose: to taunt Disney. When a reporter asked about the ad’s meaning, MCA President Sidney Sheinberg said, “Let everyone wonder…Let Disney wonder.”

Six months later when another reporter asked about MCA’s plans to build in Florida, Sheinberg quipped, “There’s a lot we’re not telling you. We don’t knowingly intend to help the competition”—meaning, of course, Disney.

On December 10, MCA finally announced that it would indeed develop a theme park in Orlando, now called Universal Studios – Florida, with a new infusion of cash from the Cineplex Odeon Corp., an entertainment company located in Toronto. The park would be similar to the Universal park in California. “But will include more attractions,” a spokesman added, meaning more stand-alone rides similar to those found at a Disney park.

With plans finally announced, MCA President Sheinberg issued a statement saying that Universal Studios – Florida “will successfully compete with any other theme parks that might seek to mimic or capitalize on the highly successful experience we have developed.”

For the public, Disney played nice, officially welcoming MCA to Orlando. “We look to every new attraction that draws vacation and convention visitors to Central Florida as an ally in bringing more people to greater Orlando in general,” a Disney spokesperson said.

But in private, Disney was already working on its next strategic move. The rationale went like this: if Universal was going to push its way into Disney’s territory, then the Mouse wanted to get in on Universal’s action in California.

A few weeks after the MCA announcement, Disney officials entered into quiet negotiations with the City of Burbank to acquire a 40-acre parcel for a new California attraction.

These talks started innocently enough. Mary Lou Howard, currently a Burbank Councilwoman and previously the city’s mayor, contacted Disney CEO Michael Eisner to see if the Disney organization would help save a proposal to build a local Towncenter mall, as key retail businesses (such as Robinson’s) had recently withdrawn their support leaving the entire project in jeopardy. After multiple phone conversations, on Jan 22, Eisner invited Howard to lunch in the executive dining room at the studio, a meeting to which she also brought Burbank City Manager Bud Ovrom.

Howard recalls, “He [Eisner] told us right away he wasn’t interested in being involved in the Towncenter, but he began to describe what he and Disney would like to do with the property.” Over a two-hour lunch, Eisner repeatedly drew pictures on napkins and even on the tablecloth to illustrate his ideas.

The ideas came quickly because they were largely drawn from a project the company had explored the previous year, to build a Disney festival marketplace—essentially a massive themed mall—in Dallas called the Texposition. In a joint venture with urban developer Jim Rouse, Walt Disney Imagineering sought to create high-end shopping centers that incorporated entertainment with restaurants and retail. Rouse’s team would largely oversee the retail developments while Disney created the entertainment. Unlike traditional malls, which included small retail shops but were anchored with department stores, the Disney-Rouse developments would avoid chain department stores entirely and instead anchor their properties with entertainment.

The first of these proposed ventures, Texposition would offer luxury shops, unique shows and a few rides and entertainment experiences for families during the day, including a Disney character breakfast. In the evening the property would present fine dining and themed nightclubs for adults. These clubs included The Adventurer’s Club with its décor themed to the 1930s, an industrial disco named Mannequins, and a freestanding building shaped like a cruise ship christened The Party Boat. The massive indoor mall space would include two bodies of water that also, in places, moved outdoors—one called the Texas Sea on which guests could hire gondolas and the other a jungle waterway on which guests could ride canopied boats past tree-lined banks. The centerpiece attraction, however, would be a theater-based flight simulator, similar to the one being developed for the Star Tours ride at Disneyland. Disney believed that the simulator would solve two problems: it would bring a high-quality technological theme park attraction to the mall, yet its content (film and software) could be changed to offer new experiences thereby attracting repeat visits from a local customer base.

Economists hired by Disney predicted that most Texposition visitors would come from two sources: (1) the 4.6 million people that lived within 100 miles of the Dallas area and (2) tourists coming to Dallas for conventions or other non-Disney concerns. The Texposition marketplace would not be a destination resort, like Disneyland or Disney World. Rather it would be a regional park, located in the Turtle Creek area of Dallas just off the I-78, what one Disney report called “yupscale” entertainment for a local market.

Over that initial lunch with Burbank Councilwoman Mary Lou Howard, Eisner explained the relatively new concept of a Disney-Rouse festival marketplace, something he thought might possibly work for her city. Howard and Eisner left that day on very good terms, with Howard excited about the possibilities of a Disney-produced mall in Burbank.

After discussing the matter with his team, on February 3, Eisner wrote a letter to the Burbank City Council officially declaring his interest in turning the Towncenter into a Disney-Rouse marketplace.

Over the weeks that followed, the Disney team expanded its proposal to something far larger than a Texposition-style mall. As the proposed site was so close to the studio, the Disney vision for the Burbank center began to absorb concepts being developed for the Disney-MGM park in Florida, until gradually the Burbank center looked far closer to a theme park than a retail mall. The unique space would soon be called the Disney-MGM Studio Backlot.

Among its plans, Disney intended to build new animation facilities at the Backlot that would allow visitors the opportunity to tour a working animation studio. They planned to build soundstages for TV and movie production. Assuming plans were finalized, this new Disney park would be built a mere five miles from Universal Studios in California—so close that guests on Universal’s upper lot could look down and see the massive new Disney venture rising from the city, like a beautiful billboard to advertise itself.

To most everyone in the amusements industry, the point was clear: this project, in part, was quickly becoming payback for MCA forcing its way into Orlando. In a BusinessWeek article from March, 1987, Eisner talked about the Disney/MCA rivalry: “They [MCA] invaded our turf, and we’re not going to take that without a fight.”

=== === === === ===

Click Here for Chapter Two – Studio Execs Behaving Badly

Also Available On The DHI Podcast

=== === === === ===

This article is part of the DHI reboot: From January through April, I’ll be posting up new articles and releasing new podcasts each week. I’m between projects, and with THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND coming out in March, I finally have more time to devote to the blog. Most regular visitors here already know that THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success.

This article is part of the DHI reboot: From January through April, I’ll be posting up new articles and releasing new podcasts each week. I’m between projects, and with THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND coming out in March, I finally have more time to devote to the blog. Most regular visitors here already know that THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success.

I should also point out that this DHI multi-part article is a substantial expansion to the original Disney/Universal article on the Studio Backlot that I wrote for Jim Hill Media in 2008. In the past eight years, I’ve discovered many more elements that contribute to this fascinating story. The original article, clocking in at twenty pages, is now over forty.

Lastly, even when things are slow on the blog, the DHI Facebook Group is always jumping. –TJP

Will Kindle version of the book be available?

If you mean of THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND, yes, there’s a kindle version available now.

But if you mean of this article, I hadn’t even thought of it. I’ll post the other three parts here over the coming two weeks.

Thanks for the question.

Hello

I have a special question.

In the middle of the 50s a movie was shot by director Ernst A. Heiniger for Disney. It was shot in Switzerland as “Schellen-Ursli”, probably the title in the US was “The Bell of Urs”, “Guarda” or “Chalandamarz” but I am not sure if the movie has ever been released. It could be a short film or a kind of documentation.

Do you have any idea how I can find out if the movie is still existing somewhere in an archive of Disney?

Because this movie is based on a popular Swiss child book it would be great to see the movie and I also have written a homepage about the different filmings and the one of Ernst A. Heiniger is missing.

I really appreciate your help.

Greetings

Thomas

Hi,

I’m trying to find any info about Aurel Thompson who was a Disney artist in the 40’s. I have two cartoonish airbrush paintings with hand written labels on the back that have her name and “Black Girl” and “Black Boy” as the titles. I have photos of the paintings I can send.

Best, Charles

Set of Alternative Linksbo Backlinks

Today is increasingly developing, rendering it less difficult for individuals to access computerized networks.

Until now there are many on-line gambling games which can be played by any person online.

Therefore, betting lovers no extended require to typically the casino to learn gambling, this

is fairly effortless for them to be able to play anytime and anywhere without limitations.