American Experience: Early Problems

Race and Culture at Disneyland in the 1950s

by Todd James Pierce

Yesterday I woke to find a handful of messages about an American Experience clip that had been posted on YouTube. The clip was posted by PBS to promote its upcoming show on Walt Disney. While lying in bed, using my phone, I checked the DHI Facebook Page to find the clip—also a few dozen DHI Facebook Group members sounding off about its content. Sample respondents included individuals claiming that they had just canceled their pre-order of the DVD and others saying that they would terminate their PBS support pledges. Many people said that Susan Douglas—the expert featured in the clip—simply “doesn’t get it.” I watched the clip, which featured Susan Douglas discussing how Disneyland, in the 1950s, inculcated guests with ideologies of racism and classism. My initial response was: Seriously, this is how PBS wants to market the show, by alienating and offending its core audience? Even PBS should know that the fan base for the parks far exceeds that of for the early animated features.

As I started in on my day, I mostly let the clip go, as, for months, I figured the PBS documentary would have both positive and negative takes on Walt and his work. Personally, I believe that Walt and his studio transformed animation, elevating it, at its best, to an artistic form of moving illustration. I also believe that Walt understood America’s attachment to entertainment in his development of cinematic themed space (such as Disneyland). But even within that, there’s lots of room for informed disagreement. Should Walt have invested himself more fully in animation in the 1950s rather than focusing on the park? Was the Magic Kingdom in Florida a distraction from his more serious interest in community planning? Was it beneficial to encourage Americans to have closer emotional connections to commercial entertainment through the development of a theme park? Was Walt a demanding, distant or generous manager? Was Walt justified in his HUAC testimony? And so on.

But Susan Douglas’ comments stayed with me. I wasn’t bothered so much that I disagreed with her. Rather, I was irritated that her commentary—or at least the section the producers included in the clip—seemed to reflect a deep misunderstanding of the activities of Walt Disney, the Disney Studio and Disneyland, Inc. in the 1950s and early 1960s.

For me, these concerns were focused on two opinions presented in her commentary:

- With footage of Disneyland running in the background, Susan Douglas explains that the park “in the end [was a] fake view of America. Disney held up a false mirror.” The section then transitions into an explanation of the original Disneyland layout.

This is one of the central misunderstandings presented in this clip, suggesting that there has been very little research completed either by the producers or by Susan Douglas on midcentury themed space, particularly as it relates to Disney. It’s hard to know who to blame. But regardless, Disneyland was not meant to “hold up a mirror” to America. Disneyland, specifically, was meant to represent filmic genres of the 1950s: the western, the adventure film, the historic drama, the animated feature. In recent decades, I believe that this connection has been blurred, but during Walt’s lifetime, the connection was evident.

Disneyland was designed by live action art directors to represent recognizable genre sets–including some sets that are lifted wholesale from non-Disney films. The Golden Horseshoe Saloon, for example, was literally, under Harper Goff’s direction, a recreation of the Golden Garter set on the Warner Lot that had recently been featured in Rue Morgue and Calamity Jane. The relationship between Disneyland and film was further solidified with appearances by the Lone Ranger and Mousekeeters as well as the Guy Williams stunt show in which sword duels from the then-current Zorro TV show were re-enacted on the Mark Twain Steamboat. The park was presented and advertised in such a way that its identity was clear: it was an interactive space in which guests engaged the environment of film.

then-current Zorro TV show were re-enacted on the Mark Twain Steamboat. The park was presented and advertised in such a way that its identity was clear: it was an interactive space in which guests engaged the environment of film.

Beyond this, even the most casual survey of Disneyland would reveal that the park, as a whole, was not intended to be a recreation of America. Some of the Disneyland environments (i.e. lands) have connections to filmic visions of America, such as Frontierland. But even here, the park is primarily presented as an image of the popular western film genre, not a direct image of America. To put this in cultural studies terms, the park is interested in presenting the mediated image, not the historic image. And some themed lands do not even have connections to filmic visions of America. These would include Adventureland (which paid tribute to films such as The African Queen and the Tarzan series) and Fantasyland (which, in the 1950s, was almost wholly structured around the folk and fairy tales of Europe).

But this point should be clear, especially in a biography of Walt Disney: the primary  visual connections within Disneyland are not to history but to popular genres of film. As Ms. Douglas has (or perhaps the producers have?) missed this point, many of her opinions that follow, in my view, do not rise from an informed understanding of artistic intent of midcentury cinematic themed space.

visual connections within Disneyland are not to history but to popular genres of film. As Ms. Douglas has (or perhaps the producers have?) missed this point, many of her opinions that follow, in my view, do not rise from an informed understanding of artistic intent of midcentury cinematic themed space.

- Again, with Walt and Disneyland on screen, Susan Douglas says: “Disney promotes this very small town, Midwestern, wholesome version of the country where…the U.S. has the best values in the world. It’s a very white view…There were a lot of ways in which the Disney vision either ignored…or sought to keep marginalized people in their place.”

With this comment, I’m not exactly sure where to begin. But let’s start with Disneyland, as the PBS clip is focused on the park.

Was the audience at Disneyland in the 1950s primarily white? Yes. But by the mid-1950s, Walt had become both an internationalist and a multi-culturalist. Walt repeatedly used the park to showcase cultural diversity within America, not to “keep marginalized people in their place.” Among the many ways this was accomplished was the yearly international Christmas pageant in which Disney invited cultural performance groups to the park (representing Asian, Latina/o, and Middle Eastern communities) as a means of showcasing the vitality of non-white cultures integrated into Euro-American society. Beyond this, Walt Disney, himself, opened the Mexico Street Exhibit on Main Street, co-sponsored by People-to-People and the Mexican Tourist Council, and for the remainder of his life, he supported the Native American cultural center that existed for 15 years in Frontierland. (Oddly part of the Native American village is included at the end of the Susan Douglas clip.) This is to say nothing of the planned, but unbuilt projects such as International Street and International Land.

These projects at the park are very much in line with Walt’s studio activities during the period. In the late 1950s and 1960s, Walt wanted to use the park-oriented Circlevision technology to create an understanding of world cultures through film. Walt explored the possibility of creating regional Circlevision theaters in world cities. By 1961, he had produced two Circlevision films, one on America and one on Italy and was interested in expanding international offerings. This plan, however, was never fully realized.

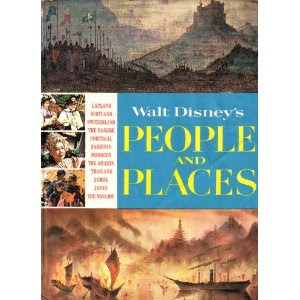

From 1953 through 1960, Walt produced seventeen theatrical short subjects for the People & Places series. These films were packaged with features and sent out to thousands of theaters across the country. Most every film focused on the culture of one world region: Alaska (Alaskan Natives), Japan, Thailand, Morocco, etc., with an eye toward bringing greater understanding to America of non-American, often non-white cultures. These films aren’t available on DVD or even VHS. In my office, I have a stack of 16mm copies of some titles as I was interested in understanding how race and culture were handled in studio projects in the 1950s. I wouldn’t expect the casual fan to track down these titles, but I would expect producers of a four-hour documentary on Walt and on-screen experts on race and Disney to have reviewed them.

At the very least, I think the People & Places films on international culture, by themselves, would negate the view that Disney consciously used film to indoctrinate its audience with the belief that “the U.S. has the best values.” Disney was certainly patriotic—admittedly more so than myself—but along with that, he was also a multi-culturalist, particularly in the last decade of his life. So this makes me wonder if any of the experts on Disney and culture in this PBS documentary examined this seventeen-film series that speaks directly to these concerns?

I think most regular visitors to the DHI site know that I’ve been interested in issues of race and diversity as they relate to the Disney workplace for a while. Could Disney have more fully integrated minority artists into the studio in the 1930s and 1940s? Certainly. Though studio artists were predominantly white, they were not exclusively white. The work of Hispanic artists at the studio, such as animator Rudy Zamora, animator Tony Rivera, and background painter Carlos Manriquez, date back to 1928, the year that Mickey was born. The work of Asian-American artists, such as storyman Bob Kuwahara and conceptual artist Tyrus Wong, date back to 1932. Moreover, the studio employed a significant number of LGB artists, particularly at WED, some of whom—in as much as the culture of midcentury America would allow—identified sexual orientation within the workplace.

I will point out that, though the studio employed multiple, long-term Asian, Latino, and Middle Eastern artists before 1950, I did notice a lack of African-American artists at the studio. The first African-American animator at Disney—or any of the Hollywood animation studios—appears to have been Clyde White, who worked there for less than three months (from May 26 to July 8, 1939). He was followed by Frank Braxton, hired in 1948, again an animator who spent a short time at Disney before building a career at Warner Brothers. Only in 1954, with Floyd Norman, would Disney establish a career-oriented African-American animator. Part of this is the studio’s fault: they could’ve done more to establish long-term African American artists before 1954. But part of the problem is a labor supply issue: from the late-1930s onward, Disney tended to hire artists directly from local art schools, with art schools themselves having a low percentage of African-American students.

I will point out that, though the studio employed multiple, long-term Asian, Latino, and Middle Eastern artists before 1950, I did notice a lack of African-American artists at the studio. The first African-American animator at Disney—or any of the Hollywood animation studios—appears to have been Clyde White, who worked there for less than three months (from May 26 to July 8, 1939). He was followed by Frank Braxton, hired in 1948, again an animator who spent a short time at Disney before building a career at Warner Brothers. Only in 1954, with Floyd Norman, would Disney establish a career-oriented African-American animator. Part of this is the studio’s fault: they could’ve done more to establish long-term African American artists before 1954. But part of the problem is a labor supply issue: from the late-1930s onward, Disney tended to hire artists directly from local art schools, with art schools themselves having a low percentage of African-American students.

But even with this, in the 1950s the studio had, for decades, defined itself as something different than “the very white” homogenous culture suggested by Susan Douglas. Moreover, in the 1950s, the professional activities of Walt Disney sought to decrease the white-centeredness of its entertainments through cultural installations at the park, the People & Places series, and various unbuilt projects. That is, the historic image of Walt Disney at this point in his life lies in direct opposition to the image of Disney presented by Susan Douglas in the clip.

Admittedly I am a little confused by the inclusion of Susan Douglas in this documentary on the life of Walt Disney. No doubt that Susan Douglas is an accomplished cultural critic and writer, but, at least on her webpage, I couldn’t find any strong scholarly connection to the life of Walt Disney or to midcentury cinematic themed space. I also realize that this clip is a two-minute promotional spot for a four-hour film. Maybe it’s merely an unfortunate blemish on the face of an otherwise well-researched and engaging project. Maybe it’s merely a two-minute misstep in a four-hour informed discussion of Walt Disney. I guess we will find out—those of us who still want to see the program—next month.

=======

For more discussion on the history of animation and themed space as it relates to the life of Walt Disney, join the DHI Facebook Group Page.

Thanks for such a well-informed response to the Susan Douglas mess. I wondered the same thing–why in the world was she included? She is a prolific writer but I can’t find anything that connects her with Disney. I wonder if she is just (as I mentioned in a couple of my facebook posts) one of those talking head generic media experts always and predictably available to PBS producers, even if the “expert” has no particular expertise on the topic. Perhaps there is a reference to Disneyland in one of her media or women in the media books. Anyway–no matter how carefully and accurately one responds to writers like Douglas, there is always the over-arching, reductive accusation of “imperialism” from which virtually no writer, artist or event can really escape.

p.s. forgot to include this. Her comments are so generic and nonspecific that they are practically doggerel, or the kind of “duck speak” Orwell writes about in 1984–essentially they are empty platitudes. Richard Schickel did a much better job and I am interested to see how he will be integrated into the program.

I was very aware of the the racism, war, economic problems and sexism. I watched the news and lived in a difficult family fighting alcoholism . I went to Disneyland to get a break from that. Disneyland didn’t say there were no problems, just that there was good too. A day at Disneyland was fun and helped this child get a break from the world. I see nothing wrong with that. I am so tired of our P C culture that sees everything through one lens. My mom’s family came from Mexico where things were very rough. They fought racism and poverty and built a great family here in the U. S.. I am very proud of them. They were given opportunity in the U. S. they would never had in Mexico. There is good to see if one looks.

I think of this from a different position. The inclusion of Susan Douglas gives those PBS viewers who are predisposed to her views a hook to watch the show, by confirming their pre-existing opinions.

It doesn’t matter if her views are correct or insightful. It looks like there is going to be a lot of content in the show for those who are interested in Disney or may already have some positive opinions on the subject.

But given PBS demographics, Disney “haters” may be overrepresented in their audience. You want to give them a reason to send in their check during Pledge Week too!

Interesting. Nothing she says in that clip is particularly untrue, but her tone is not appreciated. She’s placing the onus of responsibility on Disney to look beyond MODERN conceptions of gender, race, and class, which is very poor work as a historian. I just wrote a nice long article for a graduate class on a similar topic and how Walt’s Disneyland was about populism and optimism and how his audience was primarily white and middle class… but I didn’t fault Disney for appealing to the sensibilities of the time, as Ms. Douglas seems to be doing. Yikes. Interested to see the documentary, now, but perhaps more so to critique it as a historian and not enjoy it as a Disney fan. Heheh.

First of all, I agree with all you wrote regarding the posted clip from The American Experience. I’ve been looking forward to the show with some anticipation and also a bit of trepidation. My fear is that the show will concentrate on unsubstantiated rumor and the type of “politically correct” social analysis on display in the clip. Hopefully, there will not be too much of that and the show will be more evenhanded. I think your comments are spot on and I will look forward to your analysis of the show after it has aired. But what was really caught my eye was your comment on the first African American employed at Disney, Clyde White. Mr. White was a person whose name I had never heard, but who I believe was referred to by Borge Ring in comments on Michael Barrier’s web site. Here is the relevant paragraph:

“Hand was by upbringing an old-fashioned traditional racist. “We got a letter from an art teacher in New Orleans, He sent us artwork done by one of his best students.The guy was good, came to California and surprised us by being coal black. So we had to give him a test he couldn’t pass.” He had expected us to laugh here and our critical responses baffled him and made him angry. ”You crazy guys wouldn’t let a German soldiers into your home even though they are much closer to you than any black person.” We squirmed and protested. A question about Dave Fleischer’s particular properties as a director was answered by a snide antisemitic remark.”

http://www.michaelbarrier.com/Feedback/feedback_ring_on_hand.htm

So my question for you is do you think Mr. White was the man Hand was talking about? As a layperson/animation fan I always had a lot of respect and interest in Hand, as he was credited as Director on so many of my favorite Disney films. That paragraph made me lose a good deal of that respect when I read it. Putting a real person’s name to the event gives it additional weight particularly since I Goggled his name and found a question to David Smith in which a grandchild asked for any information on his (I assume) dead relative. The question gave the impression that the fact of his brief employment was a matter of pride in the family. So sad if he was fired based on race.

http://marciodisneyarchives.blogspot.com/2010/08/clyde-r-white-animator-at-disney-studio.html

Robert,

Thanks so much for your comment. I do not believe that Hand’s comments refer to Clyde White. To the best of my knowledge, White was from Chicago, not New Orleans. But as to your other question, let me add one thought: I would say that, as an extreme generalization, the west coast artists (particularly those who started young with Disney) tended to be more open to diversity in the studio than those the studio recruited from the New York studios. I fully believe that the 1930s were a defacto racist environment in America. I also believe that Walt, personally, was more progressive than many managers of the era. There were cultural differences between the west coast animators and the New York animators and, from the few examples I have, anecdotally, this seems to include differences in understanding of race. The few problems, like the one you cite above, that I’ve seen are mostly tied to the 1930s (as the studio swelled from 200 to 1,200 people), associated with middle management (not with Disney personally), and are not usually associated with those artists who started young in the studio and absorbed the studio’s values. From what I’ve seen most of the examples, like the one you point to, are gone by the early-to-mid 1940s, when the studio shrinks back down to 300-ish artists.

I agree with you. I have never seen any evidence of Disney having or displaying any racist or sexist attitude. There is plenty of evidence to back up your opinion that his attitude was pretty progressive for the time.

David Hand seems to have been considered pretty much “No. 2”, at least to the animation employees in the late 30’s to early 40’s though, wasn’t he? It’s easy, I think, to see how they might have misattributed Hand’s attitudes to Disney or just assumed that they were the same. I think this would particularly apply to employees who were hired from the time of the expansion until the strike. I realize I am speculating here (and as a historian you likely hesitate to engage in speculation), but I have never read any of the negative stuff popularly attributed to Disney from people who knew him personally. Although my respect for Hand was greatly diminished by his statement as quoted by Borge Ring I still recognize he was a very talented man who was, I’m sure, considered to be a valuable employee by Disney. I would suspect that Hand’s personal beliefs were the furthest thing from Disney’s mind at the time.

The ideals of the themed space at Disneyland, as Todd points out, is that of the cinematic version not the true to life version. I think what Susan Douglas is getting at is that Disneyland, in its idealization of time periods that had predominant racial tension, does not show these very struggles of minorities and marginaliz d people and therefore is from the white perspective. But I would say that the very lack of marginilization in design and execution at Disneyland shows the actual ideal of our society towards progressive inclusiveness. Disneyland didn’t glorify that marginilization and prejudice that very much existed, it wiped it away to show what these places and eras could be like without it! And to Todd’s point, it also showcased a greater ideal for knowledge of other cultures and understanding the value they have. I think a lot of this stuff can be interpreted one way or another to ones own peragative, but it’s clear to me that Walts creation, intentional or not, was quite progressive for its time.

I rented it from my local video store on 9/03. It wasn’t the tear-down of Walt that I had feared, even though some of the interviewees do question his motives and his supposed “darkness”. Some stills are out of place in the timeline, but oh well. There were short interviews with (among others) Ron Miller, who I wish would consent to more interviews while he is still able. He has a wealth of insight into WDP during the last 12 years of Walt’s life. Anyhow, I enjoyed all 4 hours, wish there was more material, especially bonus material, but there isn’t. I enjoyed it.

I came across this old piece while looking for some perspectives on Walt Disney’s depiction of America, after recently visiting Disney World. I admittedly had a reaction more similar to Susan Douglas’. I appreciate your rebuttal to her, but it brings to mind a few things. First, is the purpose of the themed parks really to recreate a cinematic space, and if so, isn’t that therefore a copy of a copy of the real thing? That still, for the visitor, evokes meaning in the real world, not in a cinematic world. Secondly, it is impossible in this era to present any depiction of American history or society without implicitly forwarding some sort of agenda, even if that agenda is that there is nothing controversial worth examining. That itself reflects an agenda, one that diminishes the real struggles of marginalized communities. So how can you say Disney isn’t engaging in that conversation when it doesn’t shy away from depictions of America and society? Finally, I was particularly troubled by Disney World’s “American Adventure” exhibit, which addresses some of these issues directly and does so in a horribly whitewashed fashion. Even if you can argue that most of the theme parks are innocent play spaces, that exhibit goes out of its way to portray a sanitized and — I would argue emphatically — inaccurate version of American history. That this isn’t acceptable in this era from an organization as influential as Disney, in my opinion.

Has that folklore map seen in the Disneyland TV footage ever been published? I’d love to see the other characters on it