In Defense of Walt

Walt Disney and Anti-Semitism

by Todd James Pierce

|

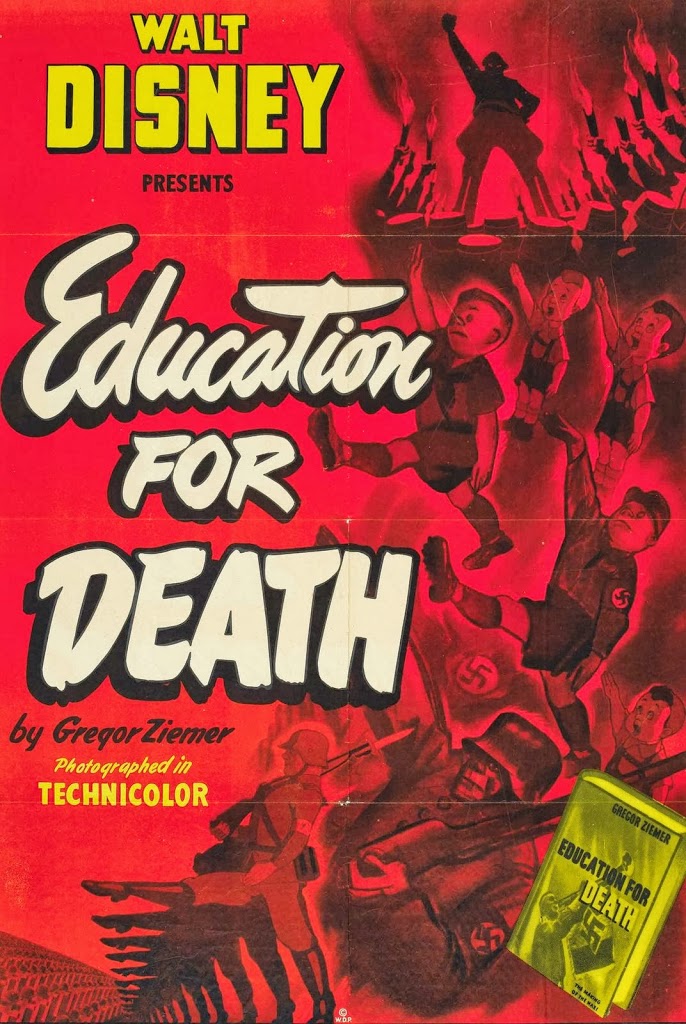

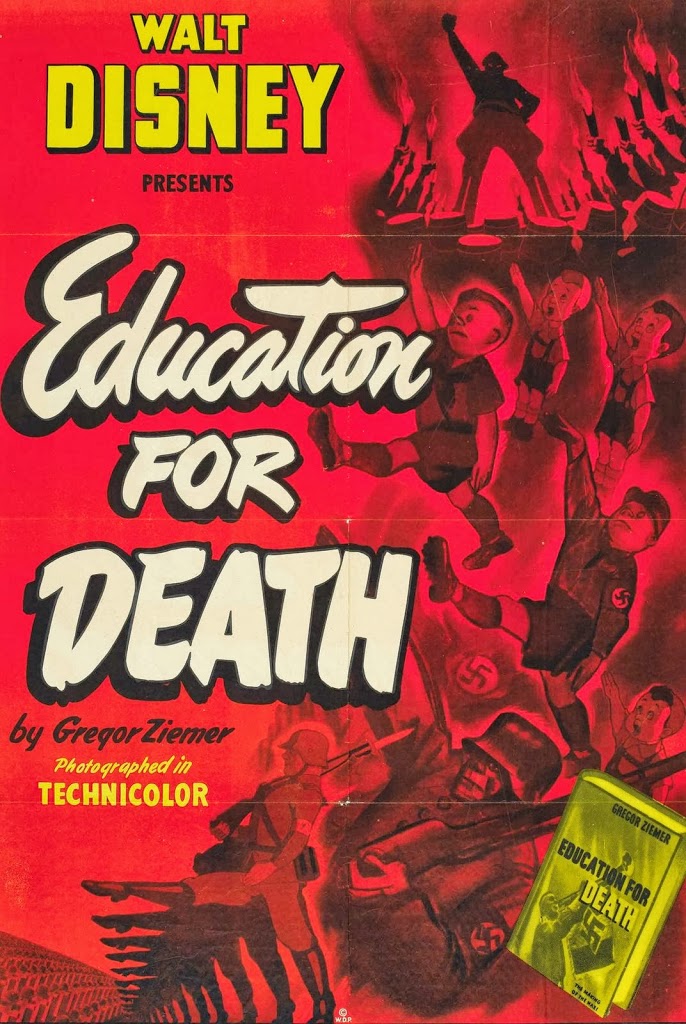

| Anti-Nazi propaganda film produced by Disney |

In recent weeks—after Meryl Streep’s comments at the National Board of Review—the internet buzzed with posts exploring if Walt Disney was anti-Semitic. I’ve gone through my materials, trying to piece together a reasonable response to these accusations, with an eye toward offering accurate information on studio activity during Walt’s lifetime and gathering evidence that presents Walt, himself—though not without flaws—as a progressive in this matter, as a man whose beliefs and practices generally advanced the roles of Jewish artists and executives in the world of film and as a man who supported Jewish causes in general.

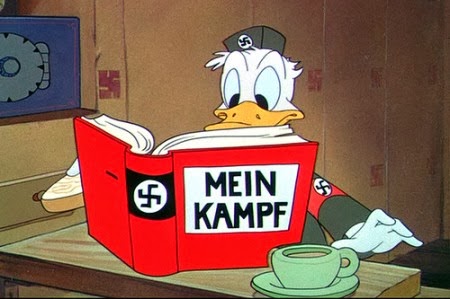

Though Meryl Streep didn’t outright call Walt an anti-Semite, the press framed her remarks in those terms—which has been a charge levied against Disney for decades. In recent years, comments about Disney and anti-Semitism have shown up on Saturday Night Live, Family Guy, and Robot Chicken. In 2007, the playwright John D. Powers produced Disney in Deutchland, a mean-spirited fantasy that concocted a fictional meeting in 1935 between Walt and Hitler, in which Hitler pitched story ideas for animated features and—even more strangely—helped plan Disneyland. Never mind that the German Board of Film had already banned a 1929 Mickey Mouse film (“The Barnyard Battle”) in which an army of malicious cats, dressed as WWI German soldiers, chased after Mickey Mouse, the Deutchland play—as with similar entertainments that depict Walt as overtly anti-Semitic—vied for attention by sensationalizing the issue of race. There was no meeting (ever!) between Disney and Hitler. In fact, shortly after the time of this imaginary summit, Walt would produce anti-Nazi propaganda that excoriated the politics of Hitler, such as “Education for Death” and “Der Fuehrer’s Face.”

|

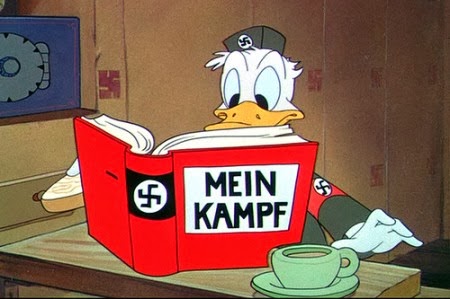

| “Der Fuerher’s Face” – Anti-Nazi WWII Propaganda film |

|

So where do these charges come from? And is there any connection between these claims and the historic figure of Walt Disney?

These claims are usually tied to two areas of Walt’s professional life: first, to his association with the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals and second, to two cartoons he produced early in his career (in 1929 and 1933).

Motion Picture Alliance

In the final years of WWII, when America strategized with Soviets to defeat Nazi Germany, some members of Hollywood believed that this political arrangement allowed left-leaning filmmakers freedom to present pro-Communist propaganda in Hollywood films. These individuals, outraged at what they believed were communist influences, formed the Motion Picture Alliance. On February 4, 1944, the MPA held its first meeting at the Beverly-Wilshire Hotel, with 75 people in attendance “representing actors, producers, directors, executives, and writers.” Their stated aim was to work against Communism and Fascism in film and American culture. Among the attendees was Walt Disney, who was voted in that night as one of the group’s three vice presidents.

During this meeting, the group’s president, Sam Wood explained that Hollywood should be “a reservoir of Americanism…for the American people, in the interests of America.” In a later formal Statement, the MPA laid out its principles, which included both political statements (to remove hidden communist and fascist propaganda from American films) and cultural statements (to preserve and present American life and history):

We believe in, and like, the American way of life: the liberty and freedom which generations before us have fought to create and preserve…Believing in these things, we find ourselves in sharp revolt against a rising tide of communism, fascism, and kindred beliefs, that seek by subversive means to undermine and change this way of life…Motion pictures are inescapably one of the world’s greatest forces for influencing public thought and opinion, both at home and abroad. In this fact lies solemn obligation. We refuse to permit the effort of Communist, Fascist, and other totalitarian-minded groups to pervert this powerful medium into an instrument for the dissemination of un-American ideas and beliefs…And to dedicate our work, in the fullest possible measure, to the presentation of the American scene, its standards and its freedoms, its beliefs and its ideals, as we know them and believe in them.

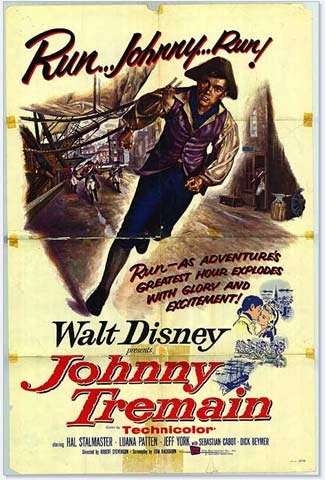

Without doubt, the cultural ideology resonated with Walt—ideals that framed later Disney projects, such as the film Johnny Tremain (1957) and the World’s Fair attraction Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln (1964). The political ideology, less so. For Walt, the connection between

communism and film was forever tied to the 1941 strike at his studio. He later explained this connection to the House Un-American Activities Committee, that Herbert Sorrell was guided by Communist influence when he organized a labor strike at the Disney Studio. For Walt, his feelings about communism and the strike were more a matter of personal injury than of world politics.

Weeks after its first meeting, the MPA filled its roster with members of Hollywood’s elite, including Barbara Stanwyck, Gary Cooper, Cecil B. DeMille, John Wayne and future president Ronald Reagan. The appeal of the MPA was, in part, tied to the war: Americans saw Nazi Germany as trying to export its ideology into greater Europe; the MPA saw its mission as to protect American film from outside influence. But shortly after its formation, liberal members of Hollywood, now threatened, formed the Council of Hollywood Guilds and Unions, which condemned the MPA as undemocratic as it sought to censor speech in film.

In 1944, the issue was partly framed through race and religion: the MPA was perceived primarily as white and protestant, tied to conservative visions of America’s past, while the Council was perceived as a committee primarily led by Jewish industry members, tied to liberal, left-leaning visions of America’s future. Celebrity Council members included Walter Wanger, Lauren Bacall, Humphrey Bogart, Danny Kaye and Clifford Odets. The ideological divide was deeply divisive in Hollywood as the industry struggled to define its own understanding of American ideas as they related to free speech and nationalism.

The ideological conflict between the MPA and the Council “caused a wide cleavage in Hollywood’s political and economic thought,” reported

The New York Times.

“It has resulted in the breaking up of some long-established writing teams and has even extended into the colony’s social life.

The factional spirit is most pronounced in studio commissaries at lunch time” as dining tables are arranged into Pro-MPA and Pro-Council groups.

From inside the studios, the battle to define Hollywood migrated to mainstream American publications to win public support. In the Saturday Review, the Jewish-American screenwriter Elmer Rice charged that the MPA was against free speech, was “witch-hunting” for communists, and presented views that he believed were “anti-unionism and—off the record, of course—with strong overtones of anti-Semitism and Jim Crowism.”

Though the MPA had offered no statements about Jews, some of its members were rumored to be anti-Semitic, even though at least five prominent members were, themselves, Jewish (writer Ayn Rand, dramatist Morrie Ryskind, director Victor Fleming, lyricist Bert Kalmar, and director Cecil B. DeMille). The MPA asked one of its Jewish members, Morrie Ryskind to pen a response. He presented the names of fifteen MPA members who were also union leaders and therefore pro-labor; he explained that most all members were not isolationists; then he confronted the charge of anti-Semitism:

Now, really, at my age and with my background (my grandfather was six-foot-two, and he had a beard that was six-foot even, which probably topped Elmer’s grandfather’s beard by at least a yard) I would be a sucker to go around joining anti-Semitic Organizations…As for the goyim [gentiles or non-Jews] in the Alliance, they work with, dine with, drink with, golf with, bowl with and play bridge with Jews; at least three of them have had the chutzpah to marry Jewish girls.

By the summer of 1944, however, it was fairly clear that public opinion was siding with the Council, particularly on issues of free speech.

Not even Cpt. Clark Gable, himself recently returned from duty overseas, could rally wide support for the MPA when he announced “he was happy to hear that an active campaign had been started against Communist groups in the motion-picture industry.”

With waning public support, the MPA began to lose membership.

But the charge of anti-Semitism stuck to MPA and by extension to Walt.

Though Walt attended meetings, after that initial gathering in February (where he was elected as a vice president) his name was never again included in any of the MPA newspaper articles published in the Los Angeles Times or the New York Times, suggesting his role was mainly a silent one. The vocal presence of the MPA was largely Sam Wood, a producer/director, as well as Howard Emmett Rogers and James McGuinness. Like many of the MPA members—which at one time numbered at least 200—Walt eventually distanced himself from the organization and its beliefs.

Ethnic Humor

|

| Original 1933 Animation – “Three Little Pigs” |

Charges of anti-Semitism also come from the type of ethnic humor in which Walt and the studio participated in its early years. The most famous example of Jewish ethnic humor comes from “Three Little Pigs,” released in 1933, in which the Big Bad Wolf disguised himself as a Jewish peddler to gain access to one house owned by a pig. The costume used by the wolf accentuated stereotypical attributes comically applied to people from Jewish descent, such as the nose, the glasses, and dress. The scene drew criticism and was later reanimated, removing the objectionable caricature, transforming the Jewish peddler into a Fuller Brush Man.

A less famous example comes from “The Opry House,” released in 1929, in which Mickey Mouse lengthens his nose and lowers his ears to perform a traditional Hasidic folk dance.

|

| “The Opry House” – 1929 |

These selections do—certainly by contemporary standards and by some standards then—show a lack of sensitivity to issues of ethnicity. But within the era, this type of visual ethnic humor was commonplace in American entertainment. The most objectionable examples of Jewish ethnic humor ended in the early 1930s at the Disney studio, but over at Warner Brothers (in the Looney Tunes series) they existed well into the 1940s.

Along these same lines, some animators remember Walt occasionally telling jokes that relied on ethnic stereotypes for their humor. The examples I’ve heard are mild and come from the earlier periods of Walt’s career. Here’s one depiction (from the 1930s) of Walt’s use of ethnic humor, as related by the great Disney animator, Ward Kimball. “For a gag, I think, Joe Grant did a caricature of [himself] and Dick Huemer [both of them being Jewish], who were working in the same department then, drawing the ‘Grant-Hume bird.’ So when the bird appeared on the end of Pinocchio’s final stretch of the nose, that was the topper, even with a nest. To top that, he had baby birds—that’s how he did it, he had a Joe Grant bird and a Dick Huemer bird, kind of an in-house [joke], and Walt says, ‘Well, jeez, if you’re gonna do that, why don’t you have a little Ward Kimball Irish bird in between them.’” The joke, of course, was that a bird modeled after an Irish animator would round out the ethnicities presented in the nest.

A Defense and Contextualization

|

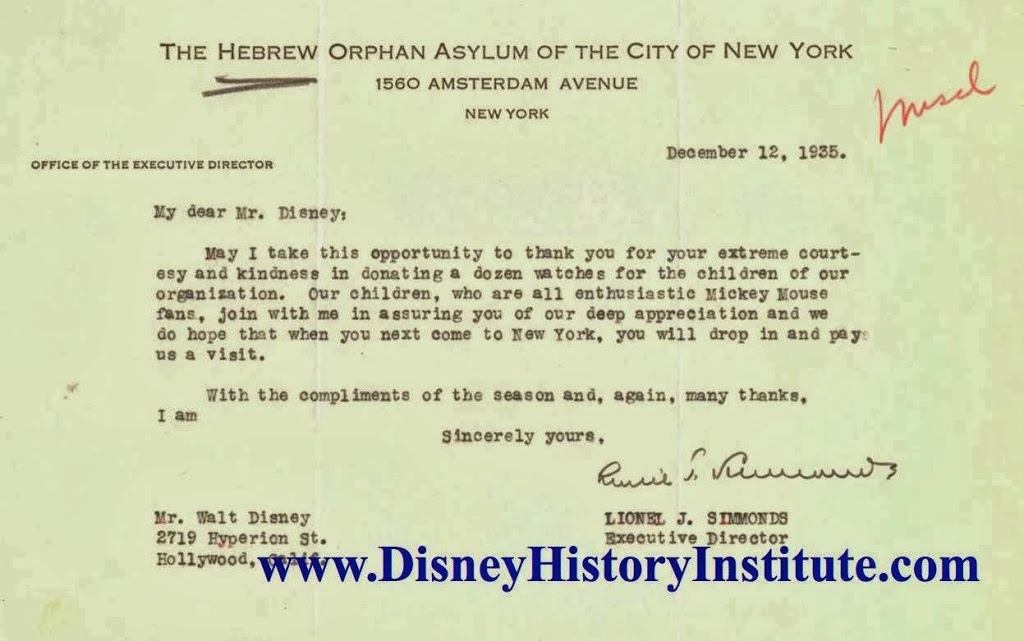

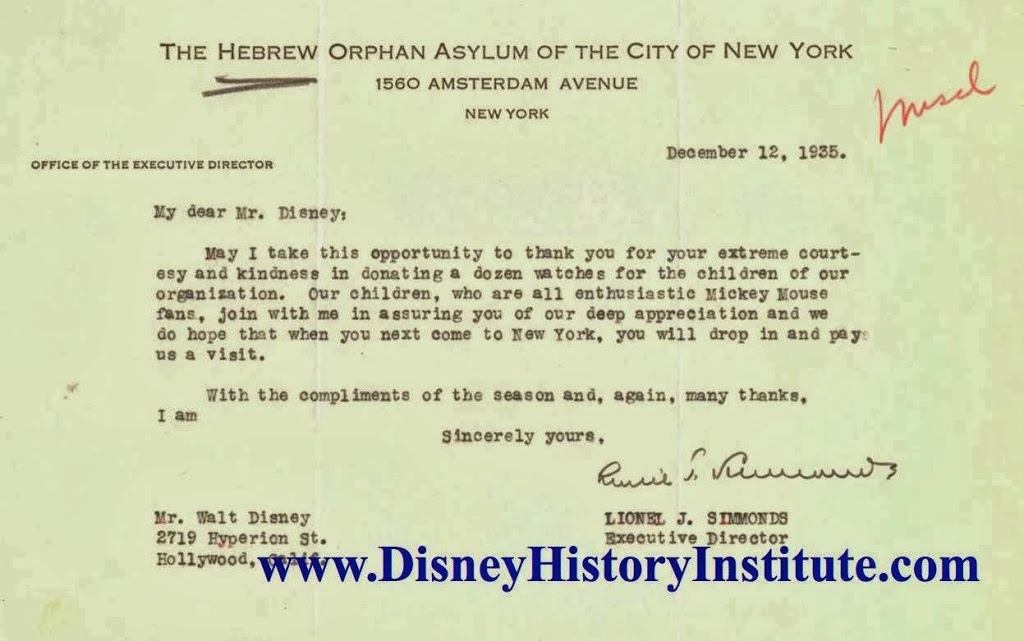

| Hebrew Orphan Asylum of the City of New York – 1935 |

In contrast to these activities, Disney had a strong and progressive connection to both the work of Jewish artists and to Jewish organizations. As has been noted on dozens of other sites, Disney donated money to a Jewish orphanage, a Jewish college, a Jewish retirement center, even the American League for a Free Palestine. As pointed out by our own Paul Anderson, Walt gave liberally to Jewish organizations (primarily children’s charities) going back to the early 1930s. In 1935, the director of The Hebrew Orphan Asylum of the City of New York thanked Walt for his gift with a personal letter: “Our children, who are all enthusiastic Mickey Mouse fans, join with me in assuring you of our deep appreciation and we do hope that when you next come to New York, you will drop in and pay us a visit.”

Robert Sherman, a Jewish-American composer who worked closely with Walt in the 1950s and 1960s, defended him with the following story: “One time, [my brother] Richard and I overheard a discussion between Walt and one of his lawyers. This attorney was a real bad guy, didn’t like minorities. He said something about Richard and me, and he called us ‘these Jew boys writing these songs.’ Well, Walt defended us, and he fired the lawyer.”

Perhaps most importantly, the studio, under Walt’s guidance, employed dozens of Jewish artists and executives, dating back to its earliest years. Jewish artists and executives worked in most every department and at high-levels of authority and expertise: from animation to publicity. Kay Kamen, a marketing genius, helped keep the studio solvent during The Great Depression. The brothers, Richard and Robert Sherman penned some of Disney’s most recognizable songs, including “it’s a small world” and “A Spoonful of Sugar.” Some of the most memorable characters in Disney’s canon were animated by Jewish-American artist Marc Davis, including Maleficent, Cruella de Vill, and Tinker Bell.

Over the past two days, I’ve assembled a list of Jewish artists employed by Disney. This list is by no means complete. It’s simply those that I could easily identify. Anyone who would like to make a charge against Walt as an anti-Semite—with the definition that Walt kept Jews from important roles within his studio—should first wrestle with this list.

Notable Jewish Artists and Executives Employed by Disney

Friz Freleng – Animator (dating back to the Alice and Oswald cartoons)

William Banks Levy – Merchandising Representative in London (dating back to 1930)

Dick Huemer – Story / Animator (dating back to the early 1930s)

Kay Kamen – Lead Merchandising / Licensing Representative (dating back to 1932)

George Kamen – Head of Merchandising in Europe (dating a back to the mid-1930s)

Robert Hartmann – Representative in the Nordics (dating back to 1934)

Hal Horne – Editor of Mickey Mouse Magazine, Publicist (dating back to 1935)

Suzanne Claire Kaufmann – Disney Office in Paris (dating back to the mid-1930s)

Joe Grant – Story / Artist (dating back to Snow White)

Otto Englander – Story (dating back to Snow White)

Art Babbitt – Animator (dating back to Snow White)

Dave Hilberman- Animator (dating back to Snow White)

Harry Tytle – Production Manager / Producer (dating back to Snow White)

Marc Davis – Animator / WED / Walt Disney Imagineering (dating back to Snow White)

Berny Wolf – Animator (dating back to 1938)

Jules Engel – Layout / Animator (dating back to 1938)

Zack Schwartz – Art Director / Layout (dating back to the late 1930s)

Dave Detiege – Writer (who also married into the extended Disney family)

Ted Berman – Story (dating back to 1940)

Irving Ludwig – Film Distribution / Publicist (dating back to 1940)

Mel Shaw – Story / Animator (Bambi)

Maurice Rapf – Writer (So Dear to my Heart, Song of the South)

Armand Bigle – Disney Representative in Europe (dating back to 1947)

Leo F. Samuels – Head of Buena Vista Distribution (early 1950s)

Lou Apett – Animator (1950s)

Ed Solomon – Animator (1950s)

Richard and Robert Sherman – Composer and Lyricist (Mary Poppins, etc.)

Mel Levin – Composer and Lyricist

Marty Sklar – WED / Walt Disney Imagineering

Sid Miller – Director (Mickey Mouse Club)

Doreen Tracey – Mouseketeer

Roberta Shore – Actress (Mickey Mouse Club serials, The Shaggy Dog)

William Lava – Composer (Zorro)

Larry Orenstein – Songwriter, Scriptwriter (Mickey Mouse Club)

Richard Fleischer – Director (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea)

David Swift – Writer (Pollyanna, The Parent Trap)

|

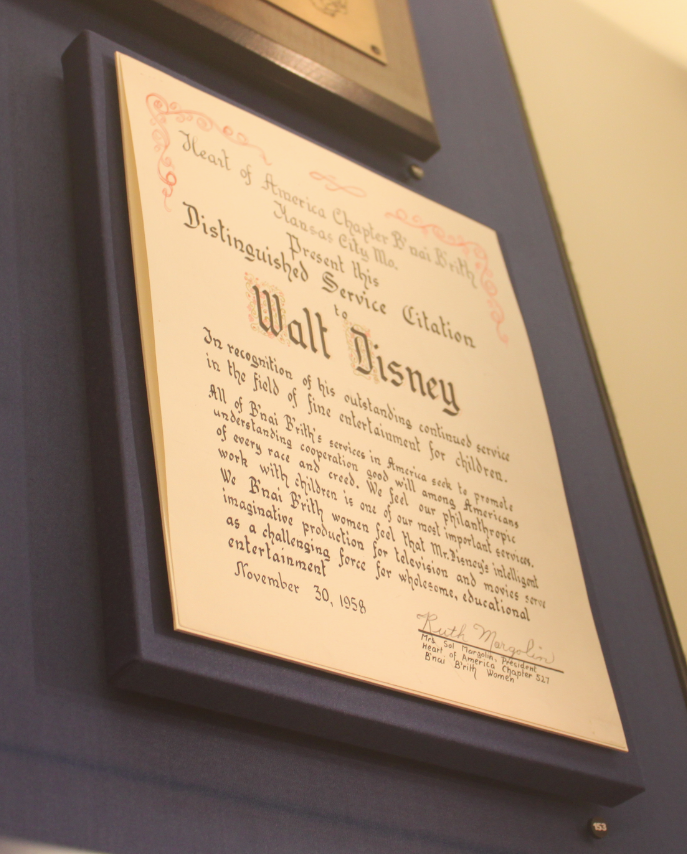

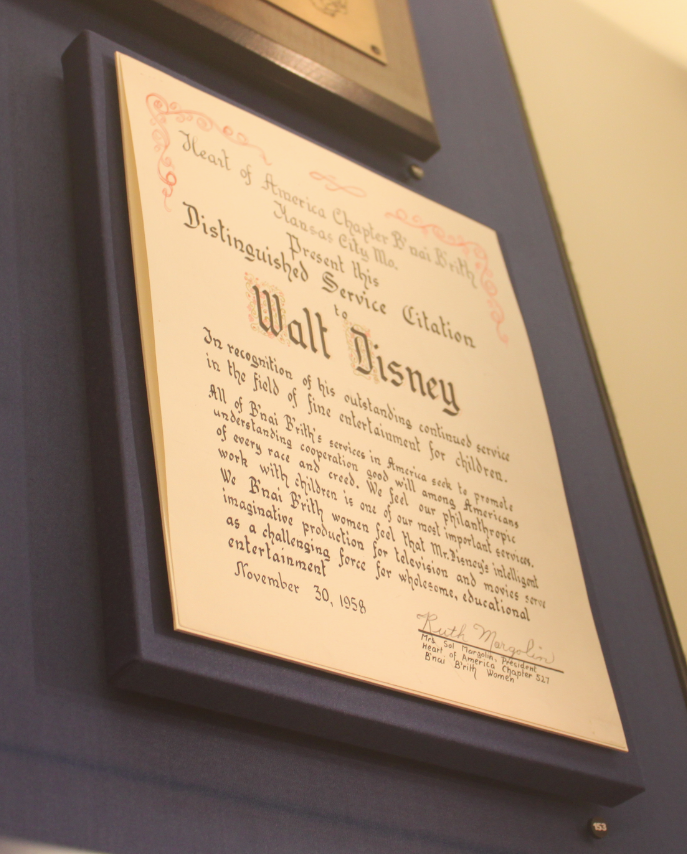

| B’nai B’rith Distinguished Service Citation – 1958 |

In ways, I’m surprised that the charge of anti-Semitism keeps returning to Walt with such force, as his own support of Jewish causes is well-documented and extends from the 1930s up through the end of his life. In 1955, the Beverly Hills chapter of B’nai B’rith (the oldest Jewish service organization in the world) declared Walt its “Man of the Year.” Three years later, in 1958, the Kansas City chapter of B’nai B’rith awarded him a Distinguished Service Citation.

Outside of the studio, Walt maintained close friendships with executives from other studios, many of whom were Jewish, including Samuel Goldwyn and Walter Wanger—who was his friend both before and after his association with the MPA.

I’m also surprised that the press, in covering this issue, approached the figure of Walt as a static individual, as though the twenty-something Walt who produced “The Opry House” was identical to the man who appeared on TV in the 1950s and 1960s. Early Disney cartoons were filled with barnyard humor and sophomoric sexual innuendo. There were, for example, a number of gags involving cow udders. The Walt who produced and approved those scenes is different in some important ways from the older Walt who championed the Toys-For-Tots campaign, created it’s a small world (which advocated for racial tolerance), and produced a series of seventeen documentary films that explored world cultures. Hardly anyone remembers the People & Places series that Walt produced in the 1950s because these films never made their way to DVD, but included in this series are thoughtful presentations on the American Eskimo, the women of a Japanese fishing village, and the desert residents of Marrakech. Most individuals—even celebrities—change and mature over time; most people, in my opinion, find that their sensitivity to others increases with age and experience.

The best example of this I can find in the life of Walt Disney concerns his feelings about Communist Russia. Two years after WWII, as America was entering the McCarthy era of Communist paranoia, Walt told the House Un-American Activities Committee in Washington D.C. that his films didn’t play in Russia. “You can’t do business with them,” he said. Twelve years later, he sent his Circlevision movie, “America the Beautiful” to Russia for a special engagement, following its appearance at the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels. In the 1940s, Walt Disney believed ideological control was crucial to limit foreign influence on American culture. But by the mid-1950s and into the 1960s, he saw film as a way of celebrating cultural differences and presenting the uniqueness of American life to other parts of the world.

================================

Lastly, a quick note: You can contact me through my

personal webpage. My most recent book,

THREE YEARS IN WONDERLAND is a detailed narrative history of the development of Disneyland (from 1953-1956), a moment by moment account of its creation and opening: the struggles, the challenges, the in-fighting and the success. You can find it on

Amazon. And remember, even when things are a bit slow on the blog, the

DHI Facebook Group is always jumping with new posts relating to the history of Walt Disney and the Walt Disney Company. –TJP

Great article, Todd. Thank you. It’s really a shame that the media now still only wants to believe this stuff. I guess if it sells newspapers they don’t really care about the truth.

As always, your article is excellent and well-researched. Not that it will change the minds of those who love the idea of Uncle Walt being a horrible person. It still amazes me that Meryl Streep would levy such accusations about a person in front of the media without being pretty darn sure of her facts first.

Meanwhile, I still remember working with a girl who was attending Cal State Northridge; she told me that one of her teachers informed the class that “Walt Disney was a Nazi”. She completely believed it. I told her that I had read a LOT about Disney and could safely say that he was not a Nazi, but I don’t think I changed her mind.

Bravo Todd! Another well articulated and researched article.

Besides Doreen Tracey, two other original mouseketeers, Judy Harriet and Eileen Diamond are also of Jewish heritage. However, I was a bit surprised to find Roberta Shore on your list, as she and her family are lifelong LDS members.

Hi George, in putting this up we had a discussion as to whether we should use the language of “Jewish/Hebrew” or simply “Jewish” to account for both religious belief and/or geographic ethnicity. In terms of language, we felt this was a difficult and complex issue. That is–we wondered what counted in terms of objectifying an individual (ethnicity or active beliefs) during the 1920s to 1960s. Many of the individuals we included on our list are, essentially, non-religious but are tied to identity through ethnicity. You’re right–she is a LDS member–but we’re under the impression she came from a Russian Jewish lineage, which is not the same as having an active faith in the Jewish religion. I would like the list to be as accurate as possible, also to highlight both ethnic and religious diversity at the studio. If you have more information, please send it our way.

Outstanding work. Thank you.

Even the Fleischer studios used exaggerated Jewish physical stereotypes in some of their characters in their 30’s era cartoons. Dave Berg who was Jewish, made fun of some of Barbra Streisand’s ‘features’ on the back cover of his book ‘Mad’s Dave Berg Looks at People’ released in 1966.