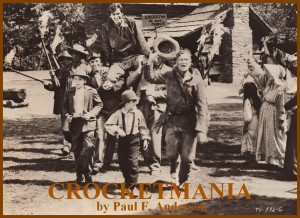

It started December 16, 1954–the day after the first episode “Davy Crockett, Indian Fighter” aired on ABC. By the second episode, “Davy Crockett, Goes to Congress,” broadcast on January 26, 1955, it was a spreading epidemic that would shortly engulf the nation’s thoughts, pastime, and psyche. It had taken Walt and everybody at the Studio by surprise. Crockett producer Bill Walsh expressed the feeling of astonishment in a Disney publicity memo, “ABC couldn’t believe it. Parker couldn’t believe it. Neither could Walt nor I. After the second episode aired in January 1955, there was no mistake. We had a hit show.”

It started December 16, 1954–the day after the first episode “Davy Crockett, Indian Fighter” aired on ABC. By the second episode, “Davy Crockett, Goes to Congress,” broadcast on January 26, 1955, it was a spreading epidemic that would shortly engulf the nation’s thoughts, pastime, and psyche. It had taken Walt and everybody at the Studio by surprise. Crockett producer Bill Walsh expressed the feeling of astonishment in a Disney publicity memo, “ABC couldn’t believe it. Parker couldn’t believe it. Neither could Walt nor I. After the second episode aired in January 1955, there was no mistake. We had a hit show.”

While not all of the merchandise boom was Disney’s, as Davy was after all a historical figure, the items that bore the “Walt Disney’s Official Davy Crockett” name were of high quality and authentic to the time period. The Crockett merchandise integrity was strictly based on Walt’s convictions. When a licensee approached Disney about doing a Davy Crockett Colt .45, Walt objected vehemently, “Absolutely not! They didn’t have Colt pistols in Crockett’s time.” His involvement in merchandising was not extensive, but he insisted upon authenticity and quality.

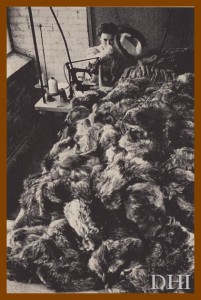

The Coonskin Cap became the classic Crockett possession. Raccoon tails, which were selling at 25¢ a pound, quickly rose to $5.00 per pound. When raccoon pelts became scarce other animals were recruited. Tom Tumbusch said it best, “If you had fur–you’d better watch out!” Even raccoon coats from the twenties became a valuable commodity.

At one point a line of caps was produced using a compound of cardboard and shredded crepe paper. This caused a nationwide alert among fire chiefs, as the caps were deemed a fire hazard. So serious did this become, that The New York Times Magazine called it a “matter of national safety.”

Books were another popular seller. The publishing industry estimates that 14 million books on Davy were sold in 1955. The previous year had averaged just around 20,000 books on Crockett. In the end it is estimated that over 300 different Davy Crockett products were manufactured.

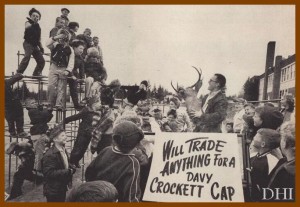

Even education was swept up into the mania. Schools were named and renamed after Davy. The naming of a school wasn’t necessarily contested, either–The New York Times reported that the Mansfield, Ohio School Board “overwhelmingly” chose Davy Crockett as the name for their new elementary school. Schools closed down when Fess Parker arrived in town for a personal appearance. One such occasion was the arrival of Fess at Hudon’s Department store in Detroit, Michigan. In this case the Detroit Public School System was “forced” to close down.

Not even the political arena was immune. Davy Crockett, once again, entered public service–not of his own volition, however. Pittsburgh voters, discouraged with their elected officials, took the opportunity to write-in Davy’s name in several primary elections. In one case, in a district election, Crockett actually won the post of Judge of Elections.

Noting the success that the Whigs had in using Crockett against President Andrew Jackson, the Republican Party considered using the Crockett image in much the same way. That was until Democratic Vice-Presidential Candidate Estes Kefauver, who was from Tennessee, beat them to it by donning (numerous times) the Coonskin cap. It did not help the Democratic ticket win the 1956 election, however.

Noting the success that the Whigs had in using Crockett against President Andrew Jackson, the Republican Party considered using the Crockett image in much the same way. That was until Democratic Vice-Presidential Candidate Estes Kefauver, who was from Tennessee, beat them to it by donning (numerous times) the Coonskin cap. It did not help the Democratic ticket win the 1956 election, however.

Then Crockett found his way to the floor of the House of Representatives again–at least his words did. During deliberation on the use of atomic energy, Texas Representative Martin Dies, read from Crockett’s 1830 speech to the House. Dies used the speech to emphasize the motto, “Be sure you’re right, then go ahead.” He further proposed that “these immortal words could be inscribed on a tablet and placed in the House of Representatives. I am sure that if they are practiced by you and me, the security, the liberty, and happiness of the Republic would be insure for all generations to come.”

An amusing situation arose from Dies proposal, as Representatives from Texas, North Carolina, and Tennessee engaged in a spirited debate over the right to “claim credit for this great American.” The debate even lead to a dispute over the birth of Crockett when Representative Jones of North Carolina submitted that Davy was born in the North Carolina territory before Tennessee had become a state. A Tennessee Congressman took exception to this. The Congressional Record chronicles his startling response, “I appreciate that what the gentleman has said is historically correct, but in view of the popularity of the present song [“The Ballad of Davy Crockett”] the record of history will probably show that he was born on a mountaintop in Tennessee.” The New York Times reported on this great debate on the floor of the House of Representatives: “Presumably fifty million kids can’t be wrong, but Davy Crockett has finally been asked to do something beyond his power. He has been asked to reform Congress.”

Besides being the focus of political fervor the intellectuals and academics got involved in the Davy debates. Brendon Sexton, Education Director for the United Auto Workers, commented on a Detroit Radio show that Davy was an “ordinary backwoodsman, who probably spat on the sidewalk, chewed tobacco, certainly didn’t know any grammar… not at all an admirable character.” Presumably because Crockett’s individualism did not suit Union needs. Newsweek suggested that “Sexton’s fusillade was his fear that the freshly venerated frontiersman might be turned into a Republican tool.”

The New York Post launched an “idol-smashing” campaign led by its labor columnist, Murray Kempton, called “The Real Davy.” Kempton’s barrage pointed out apparent inaccuracies: “He met his first bear at age of 8,” not 3; he claimed Old Betsy “was a Republican campaign contribution”; and called Davy “a fellow purchasable for no more than a drink.”

The New York Post launched an “idol-smashing” campaign led by its labor columnist, Murray Kempton, called “The Real Davy.” Kempton’s barrage pointed out apparent inaccuracies: “He met his first bear at age of 8,” not 3; he claimed Old Betsy “was a Republican campaign contribution”; and called Davy “a fellow purchasable for no more than a drink.”

Harpers and Saturday Review also joined in the heated intellectual debate; running articles with titles like, “The Embarrassing Truth about Davy Crockett” and “The Two Davy Crocketts.” Most concerned Davy’s moral character and were alarmed at the differences between actual history and Disney’s version.

A host of allies sprung to Crockett’s defense, including, oddly enough, The Communist Worker. The Worker defended Davy, “It is all in the American democratic tradition, and who said tradition must be found on 100 per cent verified fact?”

William F. Buckley, on his State of the Nation show on the Mutual Broadcasting Company, exonerated Crockett, too. “The assault on Davy is one part a traditional debunking campaign,” Buckley commented, “and one part resentment by liberal publicists of Davy’s neuroses-free approach to life. He’ll survive the carpers.” (And he did.)

Finally children came to Davy’s defense. Children and their parents, picketed the editorial offices of The New York Post. They wrote letters to Harper’s and Saturday Review, expressing their disapproval. One such letter to Harper’s, concerning the article “The Embarrassing Truth About Davy Crockett,” was from a 12-year old girl. She contended that the article was “dangerous.” It seems that she had read it to her boy friend “and was barely halfway through when he gave me a crack on my shins with old Betsy and then hit me across my nose with his coonskin cap.”

Collier’s had the most eloquent defense, explaining “Children don’t select their heroes on the basis of the exact historical record. And who can say that Daniel Boone is any more real an American hero than Pecos Bill or Paul Bunyan or Huckleberry Finn? It is he who makes the hero real, who by some childhood magic can turn a stick into a horse. The real hero is not Davy Crockett or Galahad, it is himself.”

The craze raged and so did the debate, (even though most parents and educators felt that Disney’s version of the frontiersman represented a good role model). In the end Disney’s Crockett outlasted his detractors.

Then, just as suddenly as it had started, the hysteria seemed to fizzle out. “A fad disappears when its function has ‘functioned’ long enough. When almost every child had his cap, rifle, powder horn, book and record,” says Sociologist Paul Lazarsfeld. “Then most children aren’t impressed with these things any more. The more pressure behind a fad the more quickly it’ll run out.”

“Manufacturers were shipping Davy Crockett items as fast as they could make them,” claimed Jerome Fryer, President of the Toy Manufacturers of the USA. “Then one Monday morning the phone stopped ringing and the orders stopped coming. Don’t ask me why everyone picked that day. They just did.” The craze had ended. Whether it was a sudden decline, as Fryer’s comment suggests, or a gradual decline, is open to debate.

Buddy Ebsen remarked, “It was like a skyrocket, it goes up and it comes down. But I, from the comments I get from people, think it’s still alive.” Fess Parker agrees, “What happened was that the show was an instantaneous hit in December. And there were only two one hour shows after that and they were spread over the next four and a half months–and reprieved. So it was on television twice over a six month period. Then we went into the theaters as a first run picture. And while that was happening, we made two more hours which was shown the following year–and then reshown–and then went into the theaters the next season. So there was about two years, I agree a diminishing trip, but it extended for a long, long time.”

Excellent well researched post, thank you so much.

Thank you.